So you think you may have COVID-19, and you want to get tested.

Your first problem might be finding a test, depending on where you live and how sick you currently are.

A recent survey conducted with administrators from 323 hospitals across the United States found…

Quote: “Hospitals reported that severe shortages of testing supplies and extended waits for test results limited hospitals’ ability to monitor the health of patients and staff….”

Adding: “… they were unable to keep up with testing demands because they lacked complete kits and/or the individual components … used to detect the virus.”

But let’s say that you can actually get a test for COVID-19.

When testing first began in the U.S. in January, there was only one type of assay that could confirm COVID-19. It relied on a technique called RT-PCR, or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

This process isolates and amplifies the viral code of SARS-CoV-2, which is responsible for the illness we call COVID-19.

Many of the tests completed since that day have used RT-PCR, which typically takes over an hour to produce a result.

Now there are several tests out there, using different methods and taking varying amounts of time to return results.

So why are there different approaches? And how do they all work? And how might testing help us fight the global pandemic?

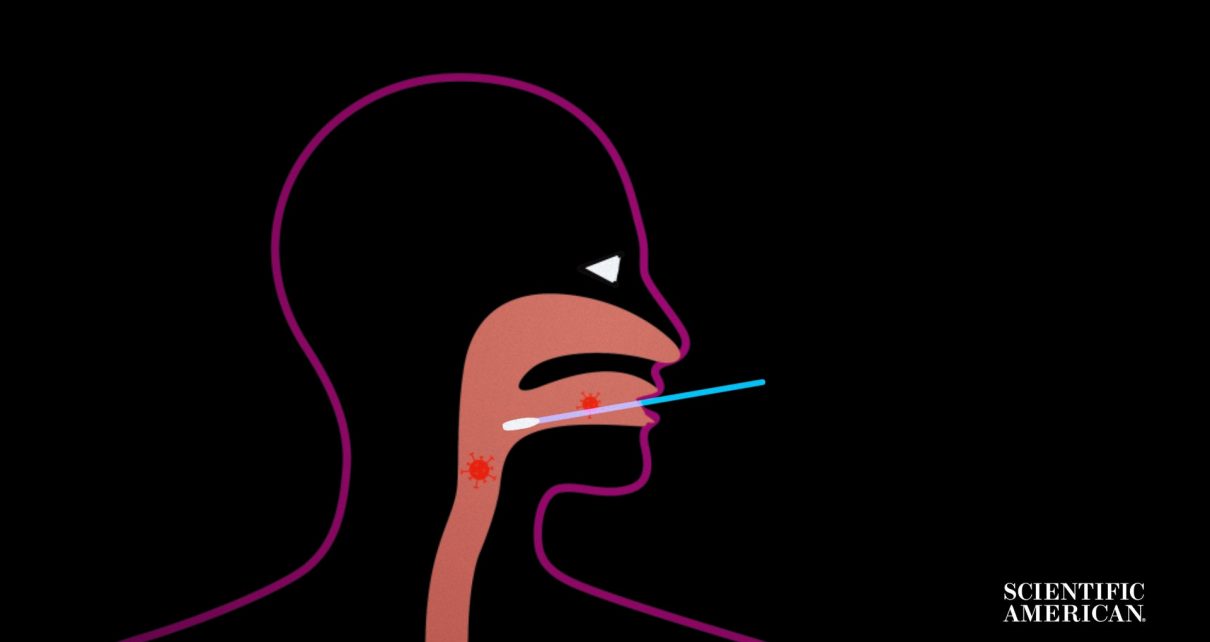

Let’s start with how the virus is collected from your body.

Many tests for active COVID-19 infection start with taking a sample from your upper respiratory tract, where the virus is known to reside.

This means pushing a collection swab deep into your nose, throat or nasopharynx, the space that connects the two.

It’s time to analyze your sample. Let’s start with the PCR part, or the “polymerase chain reaction.”

It requires that samples be processed by trained technicians on specialized machines in testing laboratories.

That means patients and the machines that test their samples are potentially far apart.

That transit time can add hours or days to getting results back, especially if the testing facility isn’t close …

… or if there is a backlog in testing.

But when analysis begins, the aim is to amplify the viral genetic code. That code is a single strand of RNA.

But the viral RNA must first be isolated and extracted from your own cells.

Once isolated, the small amounts of viral RNA must be amplified to detectable levels.

That’s where the “RT” or “Reverse Transcriptase” comes in. It takes the single-stranded viral RNA and uses it as a template to produce double-stranded DNA.

That DNA is then copied over and over using the PCR, or “polymerase chain reaction.”

PCR does this by using cycles of heating and cooling.

It breaks apart the double strand.

Added chemicals called “primers” seek out specific genes, or portions of that now separated DNA.

RT-PCR tests can target different coronavirus genes that do different things to help the virus replicate.

Some of those genes help to create the virus’s outer protein envelope. Some make its spiky surface proteins.

The point of this whole process is to exponentially increase the viral DNA with every heating-cooling step. After many cycles of PCR, one section of viral DNA in the sample would turn into millions or billions.

Large analysis machines can also run multiple samples at once. Even if they take a few hours to process, many results are returned at one time.

But the results of the test must still be collected and communicated back to you.

This causes another delay in getting your COVID-19 diagnosis.

But while the bulk of continued COVID-19 testing will probably happen this way, new kinds of tests are starting to show up.

On February 29th, 2020, the FDA issued an immediately in effect guidance that allows laboratories to submit rapid SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests to be approved for use under an emergency authorization.

This includes several so-called point-of-care diagnostic tests.

Some of these are just smaller versions of the RT-PCR machines but with prepackaged primers so that any health care worker can run the sample as long as that person’s facility owns the company’s sample analysis machine.

One of these rapid diagnostics uses a new method, called isothermal amplification.

Recently, President Donald Trump mentioned one company developing this new kind of test.

TRUMP: “On Friday, the FDA authorized a new test developed by Abbott Labs that delivers lightning-fast results in as little as five minutes. That’s a whole new ballgame….”

The testing machine is small, which means it can be located in hospitals and doctor’s offices. And “isothermal” means it detects the virus without having to go through the time-consuming heating and cooling cycles that PCR uses. Here’s how it works.

Under the hood of this test is something called a “nicking enzyme amplification reaction,” or NEAR.

It uses primers to target pieces of the SARS-CoV-2 viral code to make more copies with a kind of genetic copier-printer template.

Added enzymes find the copied pieces of viral code and “nick,” or very selectively cut, the replicated viral code out of that template like a paper cutter at the end of a printer.

And this printer prints from both ends, so it spits out two new viral sequences with every new print operation.

Each piece of viral code in your sample can be harnessed by these double-ended genetic copier-printers. This means both the printers and the copies from them rapidly increase if they detect coronavirus RNA.

Each new viral sequence copy also gets a fluorescent beacon—it’s like it leaves the printer with a streak of glowing highlighter on it.

This rapid copy print of viral sequences is what allows for a positive ID of COVID-19 in just a few minutes.

As of mid April, USA Today reported that the company had “shipped about 500,000 of the rapid tests, which run on instruments that sell for $4,500 apiece, to all 50 states, Washington D.C., Puerto Rico and the Pacific Islands.”

The last type of test is a blood test. And it is critical for finding out how many of us have been infected, and, perhaps, who might be able to return to work, and when.

It’s called an antibody test, immunoassay, or serologic test.

It works by identifying some of your body’s own defenses against the virus, called antibodies.

These proteins, called immunoglobulins, only exist inside you if you’ve mounted an immune response to the coronavirus. These tests often use a portion of the viral code to search for these antibodies in your blood.

It’s important to note that these tests are not replacements for the swab-based tests for active infections.

The U.S. FDA says as much, citing the delay between onset of infection and antibody build up.

These tests do excel at finding out who has already been infected.

Knowing how many of us have been infected and fought off the virus, sometimes with mild or no symptoms, is critical for long-term disease surveillance.

And if you’ve already had COVID-19 and lived through it, your body may know how to fight off reinfection in the future—at least for some period of time.

Exactly how long your immunity might last is an open question, though it opens up the possibility of those who have recovered returning to normal work and contact with others.

Also, if your immune response was strong enough at beating back the virus, you may carry effective antibodies in your blood.

Those would be useful to others with weaker immune responses to the virus.

In fact, the FDA recently designated so-called “convalescent plasma” as an investigational product for critically ill coronavirus patients.

This plasma could also help in the development of effective vaccines.

Regardless of what tests you take for COVID-19 in the coming months, what remains clear is that all of these methods will be necessary to beat the coronavirus and end the pandemic.