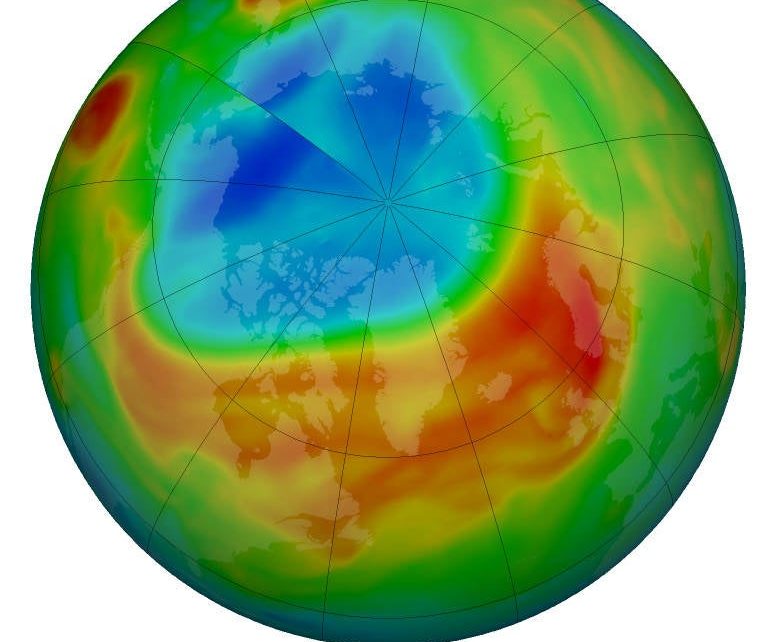

After looming above the Arctic for nearly a month, the single largest ozone hole ever detected over the North Pole has finally closed, researchers from the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) reported.

“The unprecedented 2020 Northern Hemisphere ozone hole has come to an end,” CAMS researchers tweeted on April 23.

The hole in the ozone layer—a portion of Earth’s atmosphere that shields the planet from ultraviolet radiation—first opened over the Arctic in late March when unusual wind conditions trapped frigid air over the North Pole for several weeks in a row.

Those winds, known as a polar vortex, created a circular cage of cold air that led to the formation of high-altitude clouds in the region. The clouds mixed with man-made pollutants like chlorine and bromine, eating away at the surrounding ozone gas until a massive hole roughly three times the size of Greenland opened in the atmosphere, according to a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA).

While a large ozone hole opens every autumn over the South Pole, the conditions that allow these holes to form are much rarer in the Northern Hemisphere, the ESA researchers said. The Arctic ozone hole opened this year only because the cold air was concentrated in the area for much longer than is typical.

Late last week, that polar vortex “split,” the CAMS researchers said, creating a pathway for ozone-rich air to rush back into the area above the North Pole.

For now, there’s far too little data to say whether Arctic ozone holes like this one represent a new trend. “From my point of view, this is the first time you can speak about a real ozone hole in the Arctic,” Martin Dameris, an atmospheric scientist at the German Aerospace Center, told Nature.

Meanwhile, the annual Antarctic ozone hole, which has existed for roughly four decades, will remain a seasonal reality for the foreseeable future. Scientists are optimistic that the hole may be starting to close; a 2018 assessment by the World Meteorological Organization found that the southern ozone hole has been shrinking by about 1% to 3% per decade since 2000—however, it likely won’t heal completely until at least 2050. Warmer Antarctic temperatures caused by global warming are partially responsible for the hole’s apparent shrinkage, but credit is also due to the Montreal Protocol, a global ban on ozone-depleting pollutants enacted in 1987.

Copyright 2020 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.