As coronavirus vaccines hurtle through development, scientists are getting their first look at data that hint at how well different vaccines are likely to work. The picture, so far, is murky.

On May 18, US biotech firm Moderna revealed the first data from a human trial: its COVID-19 vaccine triggered an immune response in people, and protected mice from lung infections with the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. The results — which the company, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, announced in a press release — were widely interpreted as positive and sent stock prices surging. But some scientists say that because the data haven’t been published, they lack the details needed to properly evaluate those claims.

Tests of other fast-tracked vaccines show that they have prevented infections in the lungs of monkeys exposed to SARS-CoV-2 — but not in some other parts of the body. One — a vaccine being developed at the University of Oxford, UK, that is also in human trials — protected six monkeys from pneumonia, but the animals’ noses harboured as much virus as did those of unvaccinated monkeys, researchers reported last week in a bioRxiv preprint. A Chinese group reported similar caveats about its own vaccine’s early animal tests this month.

Despite uncertainties, all three teams are pressing ahead with clinical trials. These early studies are meant mainly to test safety, but larger clinical trials designed to determine whether the vaccines can actually protect humans from COVID-19 could report in the next few months.

Still, the early data offer clues as to how coronavirus vaccines might generate a strong immune response. Scientists say that animal data will be crucial for understanding how coronavirus vaccines work, so that the most promising candidates can be identified quickly and then refined. “We might have vaccines in the clinic that are useful in people within 12 or 18 months,” says Dave O’Connor, a virologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “But we’re going to need to improve on them to develop second- and third-generation vaccines.”

Immune response

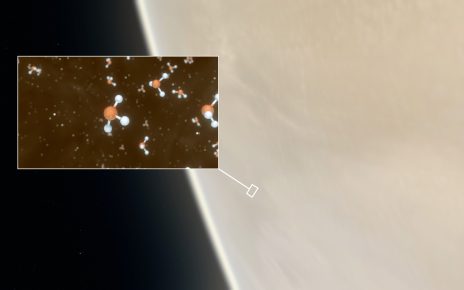

Moderna’s vaccine, which is being co-developed with the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland, began safety testing in humans in March. The vaccine consists of mRNA instructions for building the coronavirus’s spike protein; it causes human cells to churn out the foreign protein, alerting the immune system. Although such RNA-based vaccines are easy to develop, none has yet been licensed anywhere in the world.

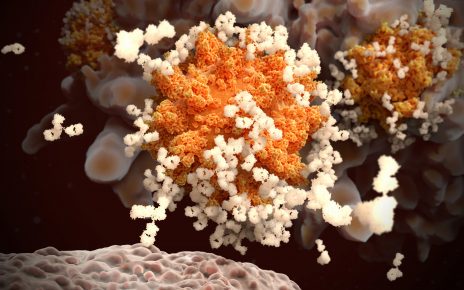

In its press release, the company reported that 45 study participants who received one or two doses of the vaccine developed a strong immune response to the virus. Researchers measured virus-recognizing antibodies in 25 participants, and detected levels similar to or higher than those found in the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19.

Tal Zaks, Moderna’s chief medical officer, said in a presentation to investors that these antibody levels bode well for the vaccine preventing infection. “If you get to the level of people who had disease, that should be enough,” Zaks said.

But it’s not at all clear whether the responses are enough to protect people from infection, because Moderna hasn’t shared its data, says Peter Hotez, a vaccine scientist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “I’m not convinced that this is really a positive result,” Hotez says. He points to a May 15 bioRxiv preprint3 that found that most people who have recovered from COVID-19 without hospitalization do not produce high levels of ‘neutralizing antibodies’, which block the virus from infecting cells. Moderna measured these potent antibodies in eight trial participants and found their levels to be similar to those in recovered patients.

Hotez also has doubts about the Oxford team’s first results, which found that monkeys produced modest levels of neutralizing antibodies after receiving one dose of the vaccine (the same regime that is being tested in human trials). “It looks like those numbers need to be considerably higher to afford protection,” says Hotez. The vaccine is a made from a chimpanzee virus that has been genetically altered to produce a coronavirus protein.

Hotez says that the vaccine being developed by Sinovac Biotech in Beijing seems to have elicited a more promising antibody response in macaque monkeys that received three doses, as reported in a May 5 paper in Science. That vaccine is comprised of chemically inactivated SARS-CoV-2 particles.

No one yet knows the precise nature of the immune response that protects people from COVID-19, and the levels of neutralizing antibodies made by the monkeys in the Oxford Study might be enough to protect people from infection, says Michael Diamond, a viral immunologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, who is a member of Moderna’s scientific advisory board. If not, a second injection would probably boost levels appreciably. “What we don’t know is how long they’ll last,” he adds.

Animal studies

Still more questions hover over experiments showing that vaccines can protect animals from infection. Moderna said its vaccine stopped the virus replicating in the lungs of mice. The rodents had been infected with a version of the virus that was genetically modified to let it attack mouse cells, which are not ordinarily susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, according to Zaks’s presentation. But the mutation affects the protein that most vaccines, including Moderna’s, use to stimulate the immune system, and this could change the animals’ response to infection.

The Oxford monkeys were given an extremely high dose of virus after receiving the vaccine, says Sarah Gilbert, an Oxford vaccinologist who co-led the study with Vincent Munster, a virologist at NIAID’s laboratories in Hamilton, Montana. This could explain why the vaccinated animals had just as much SARS-CoV-2 genetic materials in their noses as control animals, even though the vaccinated monkeys didn’t develop any signs of pneumonia. Administering high doses ensures that the animals are infected with the virus, but it might not replicate natural infections. The Oxford study did not measure whether the virus was still infectious, Diamond says, and the genetic material could represent virus particles inactivated by the monkeys’ immune response, or the viruses the researchers administered, rather than an ongoing infection.

Still, the result is “a concern” that raises the possibility that vaccinated people could still spread the virus, says Douglas Reed, an aerobiologist at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Vaccine Research in Pennsylvania. “Ideally, you want a vaccine that would protect against disease and against transmission, so that we can kind of break the chain,” he says.

One way to find out whether vaccines can prevent transmission would be to study them in animals that are naturally susceptible to the virus and seem capable of spreading it, such as ferrets and hamsters, says Reed. He and other researchers also point out that macaques display only mild symptoms of coronavirus infection, and they wonder whether vaccines should be trialled in animals that develop more severe disease.

Safety signs

Although assessing vaccines’ potential efficacy is difficult, the latest data are clearer on safety, say researchers. The Moderna vaccine caused few severe and no lasting health problems in trial participants. The vaccinated Oxford and Sinovac monkeys did not develop an exacerbated disease after infection — a key fear, because an inactivated vaccine for the related coronavirus that causes SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) showed signs of this in macaques.

Stanley Perlman, a coronavirologist at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, says that the animal studies conducted so far can tell vaccine developers only so much. “People are doing as best they can,” he says. None of the data that he’s seen should dissuade developers from pressing on with trials in humans to determine whether the vaccines work, he says.

Moderna will soon begin a phase II trial involving 600 participants. It hopes to begin a phase III efficacy trial in July, to test whether the vaccine can prevent disease in high-risk groups, such as health-care workers and people with underlying medical problems. Zaks said that further animal studies, including some in monkeys, were under way, and that it wasn’t yet clear which animal would best predict whether and how the vaccine works.

The Oxford team has already enrolled more than 1,000 people in its UK trial. Some volunteers have received a placebo, so the trial could allow researchers to determine whether the vaccine works in humans over the coming months. The lack of safety problems in the team’s monkey study was reassuring, Gilbert says.

“We don’t really need any more data from animal trials to continue,” she says. “If we get human efficacy, we’ve got human efficacy, and that’s what matters.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on May 19 2020.