I decided to write this essay because I needed something to help process everything that I am seeing and doing as a resident physician working in critical care at a large hospital in Manhattan. I feel that many people don’t have a good sense of what is actually happening in intensive care units with desperately ill COVID patients.

In some ways, I’m lucky. I work at an institution with massive resources. Even so, we are challenged in a way that I could never have predicted or imagined. In a matter of days beginning in late March, we created over double the number of ICU beds we previously had. Through a massive logistical effort, we converted operating rooms into ICUs by turning spaces that normally would be used for elective surgeries into negative-pressure units, where air is always flowing in rather than out, adding ventilators, monitors and beds.

A typical day begins at 6 A.M. As the alarm wakes me, I feel a deep ache in my body. It feels as if I had hiked up a mountain with a giant backpack the previous day. To say my sleep is restless and difficult is an understatement. My dreams—and nightmares—are populated with patients’ faces, and I can hear the constant beeps and alarms of the pumps, vital sign monitors and ventilators even as I’m falling asleep. After checking my messages (assignments constantly shift during the pandemic), I look in the mirror.

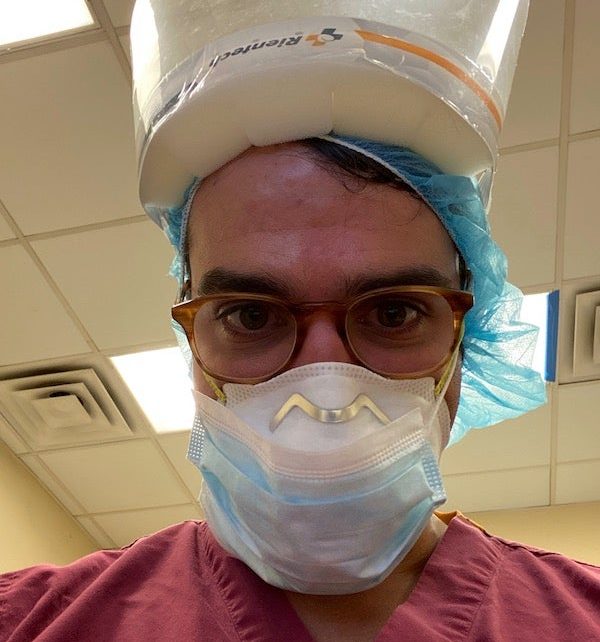

My face is still red from the N95 mask I wore the day before. My nose is scraped and red, as if sunburned. My ears have small cuts from the plastic ties of the mask digging into them. I have worn a beard for the last five years, but because N95 masks don’t properly seal with facial hair, I shaved it off. The mirror shows a face that looks odd, like a rapidly aging and graying teenager, with blemishes on my neck from the razor and the mask.

My wife and son are still asleep. My wife is also a physician, and one of the most challenging and stressful aspects of this has been the scramble to find ad hoc childcare for our son. We have had mixed success with this. We can’t have either of our parents take care of our son; it’s too much of a risk for them because of their age and because of our constant exposure to sick patients.

My wife and I have designated two paper bags to hold all of the clothes we wear to the hospital. I put on my “society” mask—the cloth mask homemade by my brother-in-law that I’ve designated as the one to wear when I’m not at the hospital. I have borrowed my sister’s car to drive to the hospital because the subways have become both unreliable and shockingly crowded at this time of day. I worry that I might be an asymptomatic carrier, or that I will be sausaged in next to someone who is sick.

I rush into the hospital a few minutes before seven, which is sign-out time for the night team. I change into hospital scrubs and shoes that I keep at the hospital and plan on throwing out at the end of this nightmare. I place a bandage over the bridge of my nose, to help pad my ever-increasing pressure burn, and place an N95 over my face. I hyperventilate to see if the seal is good.

Then I enter the ICU. I find it hard to find words to describe what this unit is like. The first sensory experience is the immense whir of the HEPA filters that whisk away over 99 percent of airborne virus-containing droplets to protect those who work in these units. It’s akin to standing next to a large industrial fan, forcing you to raise your voice to be heard—although your speech sounds garbled anyway when you’re talking through one or often two masks. There is an antechamber we’ve fashioned into a workroom with computers and monitors where we can write notes or check lab reports with a physical barrier between us and the patients. This is for our protection so that we aren’t being constantly exposed to virus.

The makeshift ICU I’m tending is full. After taking some time to review overnight data including urine output; vital signs; laboratory results; imaging such as chest x-rays; and changes to ventilator settings, it’s time to don even more protective personal protective equipment—a gown, a protective face shield and gloves—and enter the room where our patients are.

The whoosh from the negative-pressure fans is striking as we enter the ICU, joined by the symphony of beeping from monitors and pumps. Normally, an ICU has a private room for each patient, but nothing now is normal. Each patient presents unique challenges, though they all share a diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia.

The process of documenting patient information while we are in the room isn’t easy. The computers where we document our findings and enter orders for medications are in the antechamber, so we bring pieces of paper to write down data from the machines. Ensuring that intubated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, the severest form of COVID pneumonia, have their ventilator settings optimized is extraordinarily difficult. Their lungs are unbelievably fragile, and we have to take great care to keep the ventilator from causing any further injury.

To understand COVID-19 patients and their individual care needs, you have to understand what happens when we breathe. With every breath we take in, oxygen diffuses from the alveoli (the millions of air sacs in the lungs) to capillaries in the bloodstream. When we breathe out, the lungs expel carbon dioxide, transferred from the bloodstream back into the lungs; the technical term for this is “ventilation.” (In pulmonary physiology, we distinguish between oxygen exchange and carbon dioxide exchange, though they are happening simultaneously.) COVID pneumonia patients have difficulty with both the uptake of oxygen and the removal of CO2.

In the weeks during which I have taken care of these patients, we’ve had success delivering oxygen to them on the ventilator, but their CO2 exchange is highly impaired—a common problem. They become hypercarbic, with excess carbon dioxide remaining in the blood. The reason could be because the lungs are highly inflamed with fluid and mucus.

During the pandemic, time both compresses and elongates. The day passes by in a frenetic whirlwind, and the toll on the body is harsh, yet a 12-hour shift can feel like a 24. In a normal ICU, most patients are very sick, but rarely is every single patient continually unstable. So both my brain and hands are constantly focused every second on stabilizing and optimizing each patient. Every hour, or sometimes more frequently, the team in the ICU goes over a list of each patient’s active treatment issues: Are the kidneys failing? Are there thromboses? Do we need to add antibiotics for treatment of a bacterial pneumonia on top of the viral COVID pneumonia?

The mindset I bring to the job has had to change significantly over the past few weeks. Much of what I learned in medical school and as a resident has helped me assume my role in the intensive care unit, but this virus has also deeply humbled all of us. At times, I feel as though we need to change our perspective and acknowledge that much of what we have learned in the past about acute lung injury from viral pneumonia may not apply to this novel virus.

Normally, I work in ICUs with postsurgical patients whose disease process is often self-limited; patients quickly get better or worse. COVID-19 patients are different. The virus seems to take weeks, not days, to truly reveal how it will affect a given patient. I have had to suppress my desire to constantly tweak and change ventilator settings—normal behavior in an operating room where I spent most of my workdays prior to the pandemic. With COVID-19 patients, the changes that I want to make to the ventilator, in the hope that one day we can remove their breathing tube, have to be slow and incremental. It seems that a patient will take a step forward towards removal of the breathing tube one day, then the next day move two steps back.

I will admit, there are times that I feel overwhelmed by the magnitude of this task. But there is one story of recovery that has inspired me to keep going. Several weeks ago (it feels like a lifetime), we were paged to the ER for a patient in respiratory distress. I was astonished to find a person in their early 30s, with no known past medical history, laboring to breathe. This patient was a year younger than I am. We had to place a breathing tube and the patient remained in the ICU for two weeks, often gravely ill. One day in mid-April, I was overjoyed to find that the patient had been removed from the ventilator and had left the ICU. This young person has a chance at a normal life (although they may require a very long recovery still). I often remind myself about this patient after a particularly difficult or stressful shift.

At the end of the day, the night team arrives, and we brief them on patient status and treatment plans. Typically, nights are controlled and quiet in an ICU, with some exceptions, but not in these units. Weekends, weekdays, nights and days are completely irrelevant; it’s as if time has stopped since the virus arrived.

After sign-out, I drive home in a daze, still distracted by the day’s events. I have to consciously remember that I am driving on the West Side Highway and refocus my attention to the task at hand. Sometimes I’ll listen to music on the way home. The pandemic has sadly helped me discover how amazing a musician the late John Prine was—another victim of COVID-19.

People often talk about health care workers as soldiers or troops “on the front lines.” I think this is an imperfect analogy. While there is no doubt that we are putting our lives on the line every day, our intention is not to make war on this virus, but to heal people. Still, I do have one thing in common with many men in uniform: my wife shaved my head into a buzzcut because my barber has been closed for the last month.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here, and read coverage from our international network of magazines here.