On Tuesday headlines around the world hailed a common steroid drug as a “breakthrough” treatment for the most severe cases of coronavirus—based on findings from a large, randomized controlled trial in the U.K. The findings, announced in a press release, have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal. But experts say there is good reason for optimism.

“This is a major, major breakthrough. I cannot overstate how important this is,” says Sam Parnia, an associate professor of medicine and director of critical care and resuscitation research at NYU Langone Health. He cautions that neither he nor his colleagues have seen a published manuscript. But he notes, “This is coming from very reputable group, with a very large sample size.”

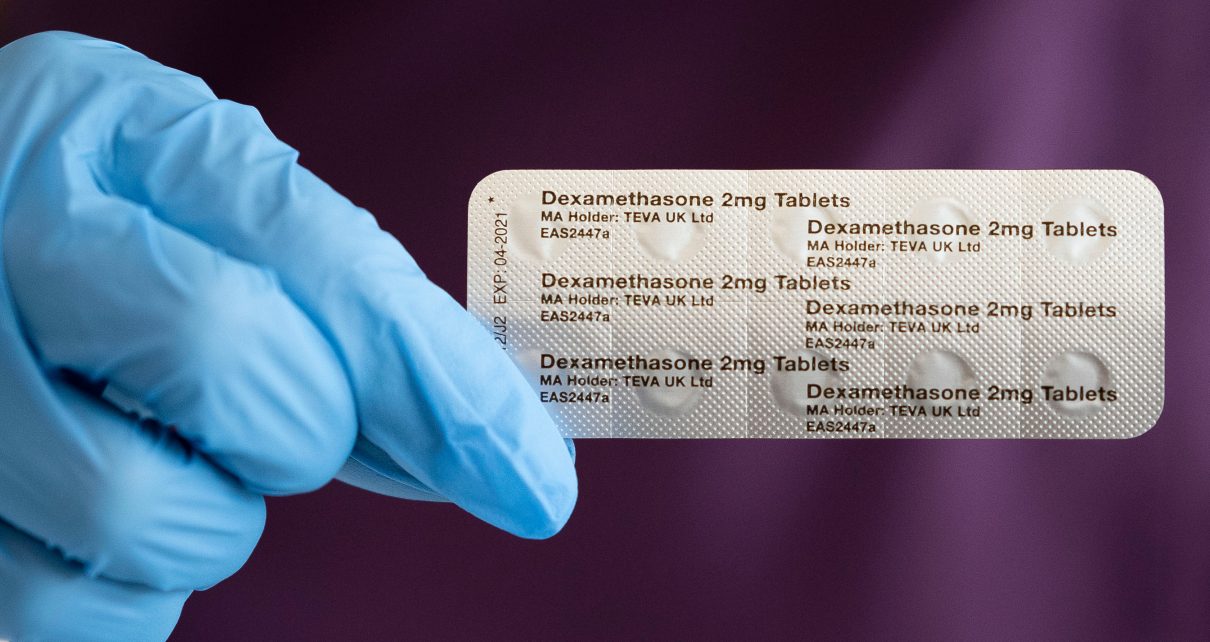

The Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial involved 2,104 people hospitalized for the illness who were randomly assigned to receive the common corticosteroid drug dexamethasone. The medication is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. A control group of 4,321 patients received only standard care. The drug reduced deaths by one third among patients on ventilators and by one fifth among those receiving oxygen therapy alone. It did not have any benefit for patients who did not need breathing support. The findings suggest that the steroid treatment would prevent one death for every eight ventilated patients or one death for every 25 patients getting oxygen therapy, the researchers say.

Given the pace at which science has been moving—and the fact that a number of highly touted “treatments” have since been withdrawn from use because they were found to be ineffective or harmful—there is good reason to proceed with caution. Corticosteroids are hormones that are often used to suppress inflammation. But they can sometimes have serious side effects. If they are given too soon in the course of an infection—or given to someone with only a mild infection—they could prevent the body’s own immune system from fighting the virus effectively. Some studies have used corticosteroids to treat other coronaviruses, including SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) or MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome), and found they were not very effective, says Stanley Perlman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa. “The [new] data need to be peer-reviewed and carefully analyzed,” he says.

But unlike the new investigation, the SARS and MERS studies were not all randomized controlled trials, and the data were not as high-quality. At least one small study of corticosteroid treatment for COVID-19, published in May in Clinical Infectious Diseases, found it improved clinical outcomes in moderate to severe cases. And doctors in many hospitals have been giving their patients steroids and noting anecdotal improvements.

Scientific American spoke with Randy Cron, a professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, about the significance of the RECOVERY findings and why he’s optimistic about steroids as a treatment for patients hospitalized with the most severe coronavirus infections. Cron is an expert on cytokine storms, the out-of-control immune response that can occur in some illnesses, including COVID-19. Although the new results have not yet been published, he says he is confident that corticosteroids are a promising avenue for treatment for several reasons. “They’re likely to work, they’re cheap, and they’re available worldwide,” he says.

[An edited transcript of the conversation follows.]

What do you make of the recently announced findings?

My overall take on this is that corticosteroids are likely to be the way to help the planet. Other drugs are expensive and not available worldwide. I wasn’t surprised when I saw the announcement. There was another report out there—not a randomized trial, but a historical cohort control study out of Michigan [the May Clinical Infectious Diseases study]. It also suggested [corticosteroids] could benefit COVID-19 patients. We used steroids for variety of cytokine storm syndromes long before COVID-19 came along. It makes sense that they would work [for COVID-19]. There have been a lot of case series [studies] of [other immunomodulators such as inhibitors of interleukin-1] (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which are also saving [the lives of people with COVID-19]. The big take-home message isn’t so much that steroids work but that the virus is [just] the trigger. And really what’s killing people is the immune response to the infection.

Weren’t some scientists hesitant to use corticosteroids to treat COVID-19 because of the risk of weakening the body’s response to the virus?

The [World Health Organization] and a lot of other groups [have, until now, been] opposed to using steroids for COVID-19. A lot of that was based on [studies of] SARS and MERS (other deadly coronaviruses), [but] the data are kind of mixed—a lot of them are not great data. Some important things to note: The timing of [when the drug is given] is important. So is the population treated—this is not something you should be giving to people who are asymptomatic, to people who are [well] enough to ride it out at home with a flulike illness or anywhere in between. The [ideal] patients are the ones who are sick enough to need hospitalization for respiratory distress from COVID-19. And you should treat them prior to the point that they need to be invasively mechanically ventilated or otherwise require intensive care. In terms of timing, the first five to seven days of symptoms are probably not when you want to treat the patient. When the patient is in respiratory distress requiring hospitalization—that’s the point when you want to dampen the immune system. Likely the dosing is [also] important. You probably don’t need to use the high doses used [to treat] cytokine storms [in other diseases]. Moderate doses may suffice.

Dexamethasone and other steroids are broad-brush treatments that suppress the immune system as a whole. How do these compare with drugs that are targeted to specific immune system molecules, which are also being tested against COVID-19?

This is a worldwide pandemic, and we’re not immune to it. In this country, [roughly] two million people [have been] infected. My guess is it’s more like 20 million if we tested everyone. If [up to 20 percent of them] need to be hospitalized, you are not going to have enough targeted [cytokine-blocking drug] therapies available. We will have enough corticosteroids. The downside is there are more side effects. If you have those more targeted drugs available, sure, you should use them. But if you’re in a country where you don’t have them, corticosteroid drugs could be a more feasible option.

What about side effects?

These drugs definitely will have side effects. Steroids are problematic; there’s no doubt about that. But if the choice is [potential side effects versus] death, side effects may be a relatively small price to pay.

Studies of steroid treatment for SARS and MERS infections found little or no benefit. Why should it work for COVID-19?

Some studies showed [steroids] helped. Some [found] they do more harm than good. Some were randomized [studies]; some were not. Some were controlled; some were not. Now we are so inundated with data—this is way bigger than SARS or MERS in terms of the numbers [of individuals] infected.

I’ve talked to people all over the world. A colleague at Temple University in Philadelphia reports their center has treated more than 1,500 individuals [some of whom were] not in a clinical trial. Everyone admitted [to the university’s hospital] gets a moderate dose of corticosteroids. Many patients were from the inner city and had a lot of comorbid conditions. Approximately 50 percent were African American; 30 percent were Hispanic—[all groups that are disproportionately at risk of severe COVID-19 infections]. Their mortality rate was under 7 or 8 percent. I’m pretty convinced [that corticosteroids are effective for severe cases of COVID-19 pneumonia].

The U.K. is now making dexamethasone a standard of care for patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19. Do you think this decision is justified?

It’s likely a better standard of care than [the antiviral drug] remdesivir. We’ll see if that’s the right decision. Even the kids who are getting [an inflammatory syndrome post-COVID-19 infection]—they do well on steroids.

Any words of caution?

The [biggest] concern I have with steroids is that people are going to want to start taking them at home—that’s not a good thing. This is really for hospitalized patients under the care of a clinician.

We’ve seen other drugs being touted as treatments for COVID-19 before. Why should this one be different?

[Most of those treatments] were being driven by infectious disease doctors, not doctors who treat cytokine storms. [Many of the drugs were] antivirals. There is going to be more steroid data coming out, but it’s going to lag [behind that on] antivirals.

Of course, we can’t really know how significant the new findings are until they are published, right?

We have to look at the data. [But] I think the concept is correct.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.