On June 5, 2020, the U.S Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published the details of a recent multistate outbreak of mumps in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). The outbreak involved 62 cases linked to a single asymptomatic wedding attendee. Even though mumps is a vaccine-preventable disease, 41 of the individuals infected in the reported incident had been fully vaccinated according to the current guidelines. What started as a mild illness in a caretaker of children in Nebraska grew into an epidemic involving communities in six different states. This raises concerns about waning immunity from childhood mumps immunization.

Mumps is a highly contagious disease of children and young adults. It is caused by a paramyxovirus of which there is only a single serotype. Humans are the only known host, and infections are spread by direct contact or through droplets from the upper respiratory tract.

The infection may remain asymptomatic for an incubation period that ranges from 12 to 25 days. When symptoms are apparent, mumps can present with initial flulike symptoms, such as fever, congestion and aches, followed by a characteristic painful swelling of the jaw. The index case of the outbreak developed left ear and jaw tenderness the day after attending the wedding. Her jaw swelling was noted 11 days after her initial exposure to the virus.

In most cases, the disease resolves spontaneously within two weeks of onset. However, complications such as deafness, infertility or encephalitis—a potentially fatal inflammation of the brain—may result. Thankfully, the disease can be largely prevented by vaccination.

The history of mumps dates to the 5th century B.C., when Hippocrates described the condition as a bilateral or unilateral swelling near the ears, and noted that some patients had bilateral or unilateral pain and swelling of the testicles. Isolation and culture of the virus did not occur until 1945, however, and a vaccination against it was first licensed in 1967.

Without routine immunization, the incidence of mumps would be projected to be 100–1,000 cases per million, with an epidemic occurring every four to five years. Universal vaccination has been a crucial factor in the global decline in the incidence of mumps. Finland was the first country to declare itself mumps-free, in 2000, after a national two-dose vaccination program for children, resulting in high vaccination coverage. In Korea, the mumps vaccine was included in a national immunization program in 1985, and booster doses began in 1997.

Sadly, according to the World Health Organization, the mumps vaccine had been introduced nationwide in only 122 countries by the end of 2018. As of June 2020, Japan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and most countries in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa did not have the mumps vaccine included in their national immunization programs.

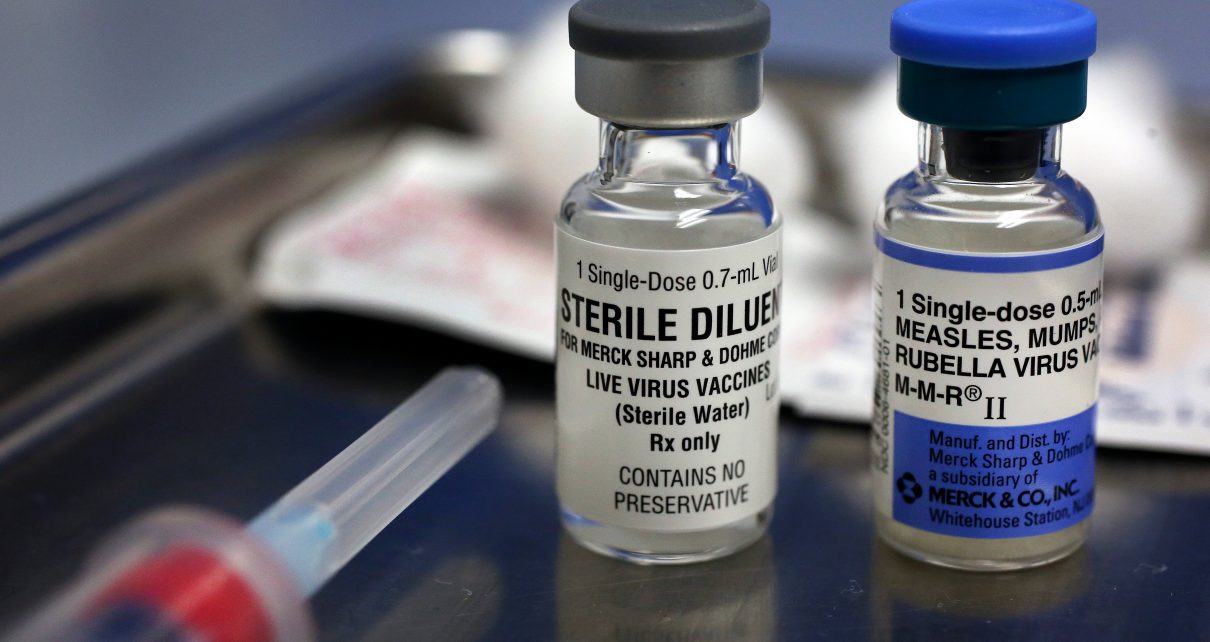

In the United States, the CDC recommendation for childhood immunization against mumps is a two-dose series. The first shot is given at 12–15 months of age; the second at 4–6 years. A catch-up vaccination may be done for unimmunized children and adolescents, with two doses given at least four weeks apart. This is especially recommended for at-risk groups such as post-high school students, health care personnel and international travelers. The mumps vaccine is given along with vaccines against measles and rubella, a combination known as MMR. It confers a 78 percent risk reduction following one dose rising to 88 percent after receiving two doses.

Although the two-dose vaccine series appears adequate to protect the general population, outbreaks such as the Nebraska incident described in the MMWR raise valid concerns. Such outbreaks led the U.S Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to recommend a third dose of mumps vaccine for at-risk adults.

In 2017, the effectiveness of a third dose of the mumps vaccine was demonstrated during an outbreak among vaccinated students at the University of Iowa. The recent incident in Nebraska lends support to the approach. According to the MMWR, a communitywide MMR vaccination campaign helped end the outbreak. So, the question we need to answer is this: should everyone who has completed the two-dose vaccine series for mumps receive a third?

Another important issue raised by the Nebraska incident is that of quarantine. The isolation of ill people was the second approach that helped to quell the outbreak. As the world continues to respond to the coronavirus pandemic, how prepared are we to do necessary work of quarantine and contact tracing equitably and ethically?

Unfortunately, the ongoing pandemic has led to a decline in the rate of childhood vaccinations. The occurrence of mumps outbreaks even in highly vaccinated populations and the control of such outbreaks with booster vaccines emphasize the importance of vaccination.

More research is needed to improve the efficacy of all vaccines. But in the meantime, coordinated local and global responses are needed to promote the availability and use of the vaccines that we have.