If space exploration was a popularity contest, Mars would be struggling for admirers. Once the darling of 20th-century planetary scientists, the world’s allure has cooled somewhat as other exciting locales—the woefully unexplored Venus, for example, or Saturn’s thrilling moon Titan—begin to turn more heads. But Mars is not relinquishing its time in the limelight quite yet. This summer, three new missions are launching to the Red Planet—and at least one of them could reinvigorate interest in Mars with a renewed search for life there.

On July 14 the United Arab Emirates’ Hope orbiter—the first interplanetary spacecraft ever built by the the country—is scheduled to take off for Mars on a Japanese rocket. In the same month-long launch window—which occurs every 26 months, when the planet aligns with Earth for easier traversal—it will likely be joined by China’s Tianwen-1 orbiter and lander, also a first mission to Mars for the rising space power. And NASA’s Perseverance rover, the U.S. space agency’s latest effort to hunt for life on the planet, will probably launch in that window as well. A fourth mission, Europe’s Rosalind Franklin rover, was supposed to join this Martian armada. But it was delayed until 2022, in part because of the coronavirus pandemic. Nevertheless, these three missions are as clear a sign as any that the Red Planet has not lost its appeal just yet.

NASA’s exploration of Mars has been steadily consistent. Following the Mariner probes in the 1960s and 1970s, which returned the first images of the planet, the Viking 1 and 2 landers became the first—and still the most ambitious—missions to search for Martian life. While inconclusive, the Viking landers were followed by subsequent orbiters and rovers, culminating in the Curiosity rover’s landing in 2012, that have painted a fascinating picture of what the world was once like. “We’ve learned that Mars has a diversity of habitable environments,” says astrobiologist Kennda Lynch of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston. “People are more positive for potentially being able to find evidence that life, in some point in Mars’ past, existed.”

Perseverance is the next step in that journey. The rover is now scheduled to launch between July 30 and August 15, after a slight delay due to the late discovery of a minor hardware problem in the final stages of testing. If all goes as planned, it will touch down in a fascinating region of Mars known as Jezero Crater on February 18, 2021. Measuring 45 kilometers across, this crater is home to a multi-billion-year-old river delta, an environment that may have preserved clear signs of life on the early planet.

“This is an impact crater that has ancient river valleys over 3.5 billion years old that fed water into the basin of the crater, a standing lake about the size of Lake Tahoe in the U.S.,” says Timothy Goudge of the Jackson School of Geosciences at the University of Texas at Austin, who led the case for Jezero during the landing site selection process. “It’s not the only delta on Mars, [but] it’s one of the best-exposed. Lakes on Earth are very good habitable environments where life flourishes. And delta deposits can preserve a record of any potential life that was extant within the lake.”

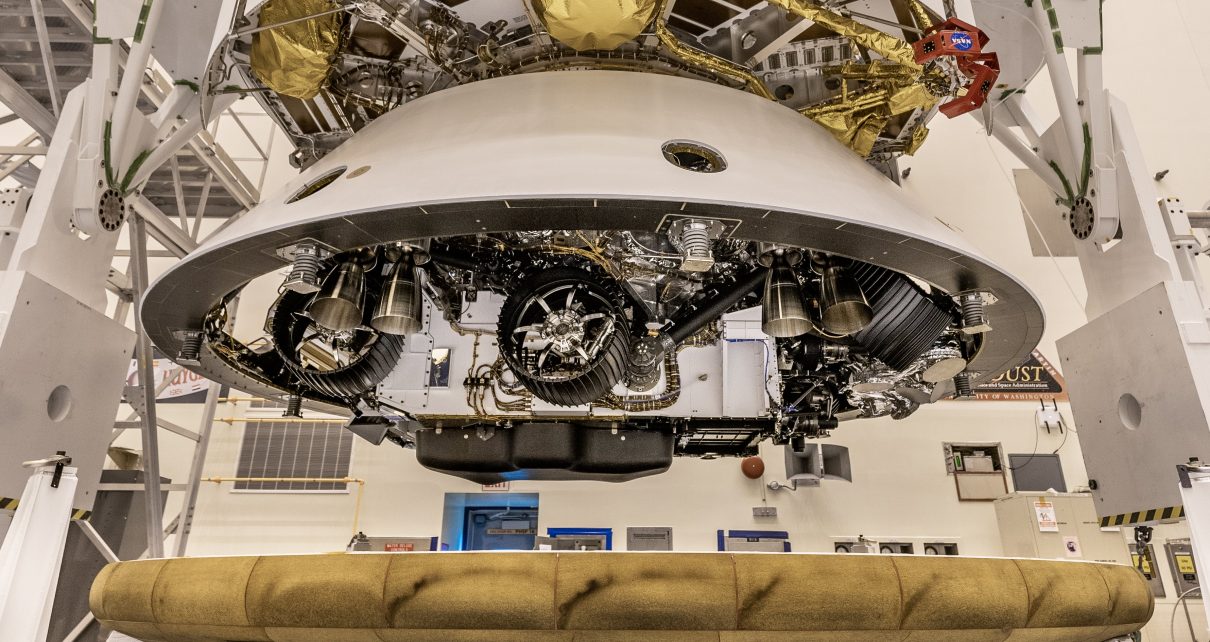

Armed with a suite of instruments, Perseverance will probe this region in exquisite detail. In some respects, the rover is a twin of Curiosity: the two outwardly appear almost identical. Their landing systems will match, too. Both use the same sort of autonomous, rocket-powered “sky crane” platform that previously lowered Curiosity on cables to a gentle, pinpoint touchdown on the Martian surface.

While similar in appearance to Curiosity, under the hood, Perseverance is a vastly different beast. The rover has benefited from a number of upgrades, including an improved, more precise landing system and hardened wheels to better cope with the rough Martian terrain. And whereas Curiosity’s tools were suited to assessing the habitability of Mars, Perseverance will be more focused on the hunt for evidence of life itself.

“We’re seeking signs of life, and that motivates a different suite of instruments,” says Ken Farley, project scientist for Perseverance at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “On the robotic arm, we have an instrument called PIXL, which measures the elemental distribution in a postage-stamp-sized area of rock. In that same area, we can take visual imagery with an instrument called WATSON. And we can measure the distribution of organic matter with an instrument called SHERLOC. These things together provide the most compelling way to find evidence of the kind of simple life that might have existed on Mars.”

That evidence could include signs of fossilized microbial life hidden in Jezero’s substantial deposits of carbonate rocks. On Earth, such environments have preserved ancient stromatolites, moundlike layered structures formed by primitive microorganisms. “Those could be left in the rock record as macro-sized fossils that we might be able to see,” says Kirsten Siebach, a Mars-focused geologist at Rice University. “That’s pretty ambitious. It would be a strong claim to say we expect that. But those are the kinds of things we’re looking for.” Such evidence will be examined using SHERLOC’s ultraviolet Raman spectrometer, the first of its kind on Mars. Doing so will allow the composition of rocks to be measured without first vaporizing them with laser beams (the more destructive technique employed by Curiosity).

Perseverance alone might not be able to understand this evidence, however. One of the rover’s key objectives is to collect samples of potential astrobiological significance and then store them in small caches on the Martian surface. The plan is for a future sample-return mission to land, pick up the caches and launch back to Earth in about a decade. The exact logistics of that mission are not clear, but it will likely be an international effort involving NASA and the European Space Agency that will arrive around 2028 and bring the samples to our planet in 2031. “Ultimately to really confirm the presence of biosignatures, the samples are going to have to be returned to Earth,” says Frances Rivera-Hernandez, a planetary geologist at Dartmouth College.

Perseverance has a few more tricks up its sleeve, too. An instrument called MEDA will monitor the Martian weather, while MOXIE will practice producing oxygen from carbon dioxide in the Martian air—which could be a critical tool for future human missions. The RIMFAX instrument will be the first ground-penetrating radar landed on Mars, able to detect water and ice to depths of 10 meters. And a variety of onboard cameras will reveal the rover’s surroundings in unprecedented visual clarity, producing videos of the surface, as well as detailed footage of the landing itself.

If that was not enough, the rover even has a “helicopter” named Ingenuity tucked into its belly. Weighing just shy of two kilograms, Ingenuity will be deployed and operated in the first 90 days of the mission. And it will constitute the first attempt at aerial flight on another world. “The helicopter is unlike anything we’ve ever really built before,” says Matt Wallace, deputy project manager of Perseverance at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Although mostly just a technology demonstration, Ingenuity will also attempt to take images of Mars from the air, including pictures of the rover that carried it to the surface.

Following the landing, Perseverance will spend its two-Earth-year primary mission exploring Jezero Crater, studying and collecting signs of life. After this task, the rover could be driven out of the crater to explore another nearby region, called Midway, that is rich in carbonate rocks. “People believe it is another habitable environment,” Farley says. Some house-sized rocks there could also be pieces of the planet’s mantle thrown out by the impact that formed Jezero—intriguing targets of study that could potentially yield new insights into the Martian subsurface.

Joining Perseverance at Mars will be Hope and Tianwen-1. The former is an orbiter designed to study the atmosphere of the world. Over the course of a Martian year, it will also examine the planet’s climate—including massive dust storms, one of which led to the demise of NASA’s Opportunity rover in 2018. Aside from its science goals, however, Hope is intended to signal the United Arab Emirates’ shift from an oil-driven economy to one focused on science and engineering. “Our space program and Mars mission is a means for a much bigger goal,” says Omran Sharaf, Hope’s project lead. “It’s about the future of the U.A.E.”

China’s Tianwen-1 mission is similarly a statement. The nation has already showcased its cosmic aspirations by launching humans to space, developing a space station and conducting lunar missions, including the first ever landing on the far side of the moon. Now, with Tianwen-1, it aims to prove it is an interplanetary space power, too. “It would bring a lot of prestige,” says Andrew Jones, a journalist that covers spaceflight in China. “Only NASA has been able to land and operate on Mars.”

Tianwen-1 will be slightly unusual, however. After arriving at the planet in February 2021, it will linger in orbit for months before it deploys its lander and rover and attempts a landing—perhaps in Utopia Planitia, not far from the Viking 2 lander. The rover will then drive off its landing platform and study its environs with its six instruments—including a radar device to study ice and water under the surface and a laser tool to measure rock compositions. Its intended lifetime will be three Earth months.

Hope and Tianwen-1 are worthy efforts in their own right. But it is Perseverance that will likely take center stage in this next act of Mars exploration. It is a jack-of-all-trades machine, almost comically overstuffed in its mission ambitions. Perseverance will fly a helicopter on Mars, produce Martian weather reports and even make oxygen out of thin air. Its greatest trick of all, however, is just how close it will bring us to knowing if we are truly not alone in this universe. “We’re entirely on new ground,” says Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA. “That’s what makes it so exciting.”