Since the coronavirus pandemic started spreading across the U.S. and state governments issued stay-at-home orders, millions of Americans have isolated themselves for months to avoid exposure. One result is that parents across the country have canceled pediatric checkups—and immunization levels for vaccine-preventable diseases have plummeted, a Scientific American investigation has found.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in May that routine orders of pediatric vaccines had dropped because of the pandemic. Later that month the agency released a report showing that, compared with previous years, Michigan’s vaccination coverage among children under two years old declined in the months after Governor Gretchen Whitmer issued a stay-at-home order. Angela Shen, a visiting research scientist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a retired captain of the U.S. Public Health Service, who co-authored the CDC’s report on Michigan, says that the researchers saw drops in adult vaccinations as well. Because of the declines, she says, “we have to be mindful that we don’t wind up with an epidemic of vaccine-preventable diseases.”

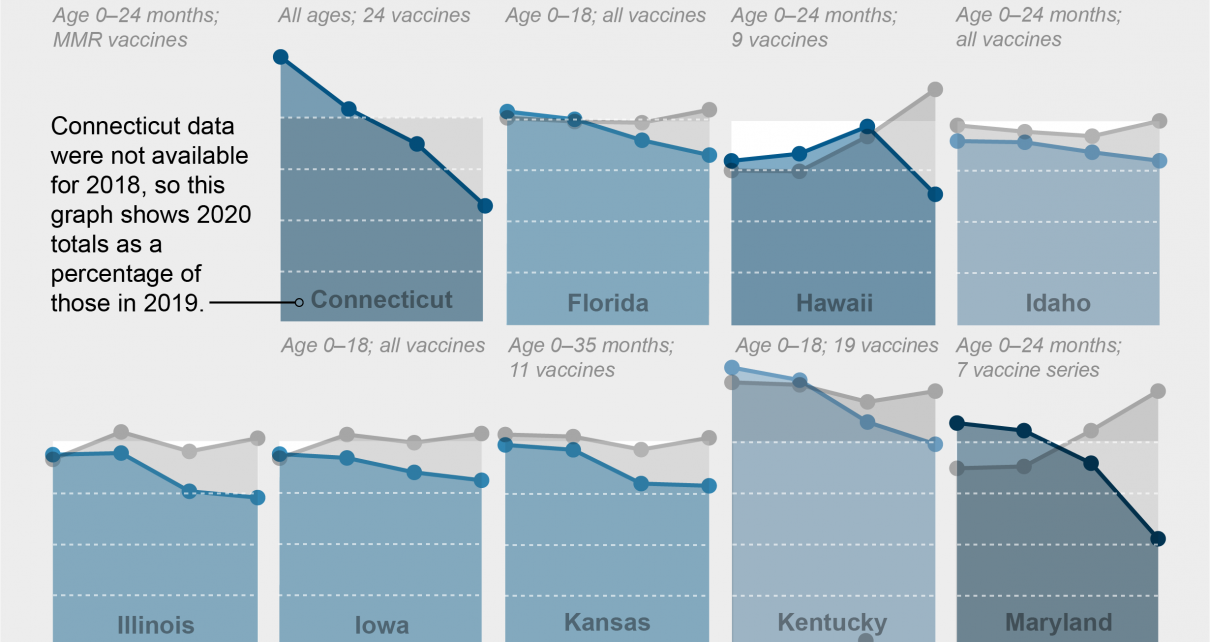

To build a more detailed picture of how the pandemic has impacted immunization levels for illnesses such as measles, chicken pox and polio across the country, Scientific American requested information from health departments in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Thirty-four agencies supplied usable data in time for this story.

States generally track immunizations by counting the total number of administered vaccine doses that health care providers report to registries and request through the federally funded Vaccines for Children Program. (The program distributes free vaccinations via state health departments and some regional health agencies.) Scientific American asked for those numbers for the first four months of 2018, 2019 and 2020. Most responding states provided totals for a suite of vaccinations typically given on a schedule before 24 months of age. Other states gave totals that included all noninfluenza vaccines issued before 35 months. And a few supplied those for all vaccines administered to children under the age of 18.

The data show that during the month and a half after the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, immunizations declined starkly across the U.S. This past March, vaccinations as a percentage of March 2019 totals were lowest in Washington, D.C. (44.4 percent). Close behind were Texas (44.7 percent) and Montana (46.8 percent). Compared with April 2019, vaccinations in April 2020 were lowest in Maryland (42.1 percent), Montana (44.2 percent) and Pennsylvania (48.1 percent).

New York City, which bore the brunt of the pandemic during the spring, closed down with the rest of New York State on March 22. The city’s health department did not provide raw data on vaccination levels. But in a statement to Scientific American, it said that by two months after the beginning of the shutdown, “administered vaccine doses [were] down 63 percent,” compared with the previous year—and that for children older than two, vaccinations dropped by 91 percent. According to data provided by the New York State Department of Health, however, vaccination coverage of children under two outside of the city remained steady—and even increased slightly, compared with 2019 levels.

Hawaii, where Governor David Ige ordered residents to stay home beginning on March 25, actually counted more vaccinations during that month than in March 2019, though they fell in April. Hawaii has had relatively few cases of the virus. Pennsylvania’s vaccination totals also stayed comparably high through March before dropping in April.

Shen says states’ public outreach efforts may have varied in their emphasis on the importance of continuing with child-wellness visits and getting shots during quarantine. That variance—along with the severity of local outbreaks and whether and when stay-at-home orders were issued—may explain some of the disparities between states.

Claire Hannan, executive director of the nonprofit Association of Immunization Managers, says every state also has a different vaccination information system. Each one tracks vaccinations differently, producing unique reports that include different amounts of data, she says. “I’m really hoping this pandemic will push us forward and help us tackle some of the challenges [in] sharing data across states and getting them on a level playing field,” Hannan adds.

Most of the responding states also provided immunization numbers for May, and they appear to indicate child vaccinations may have already begun to rebound slightly. While still well below 2019 levels, totals in these states were typically several percentage points higher in May than they were in April. Only Minnesota continued to decline—and even then, its drop in May was far smaller than that of previous months. Shen says getting immunizations back on track is critical to staving off an epidemic of vaccine-preventable diseases. State health agencies can use immunization registries and work with providers to identify families that need to catch up on shots and remind them to do so, she adds.

“As the country opens up again, we don’t want to fall behind,” Shen says. “The implications of having outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases at the same time we’re combating the challenges of COVID-19 and approaching flu season in the fall is a recipe for a lot of public health problems.”

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.