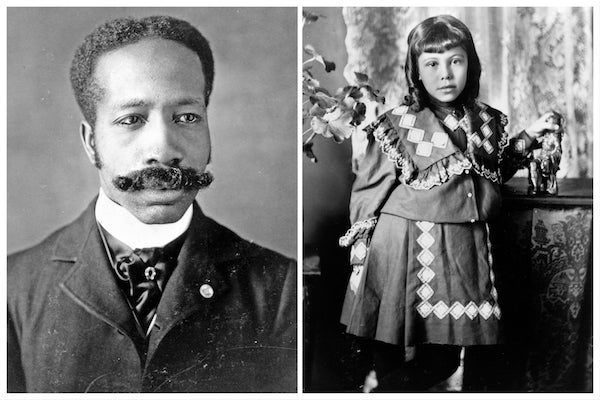

In the 19th century, the most photographed man in the world wasn’t Walt Whitman or Ulysses S. Grant or even Abraham Lincoln. It was Frederick Douglass. The famous orator and abolitionist was known for using his eloquent voice to impart the horrors of slavery, which he had experienced firsthand. He traveled all over the country, speaking to large crowds and making arguments to end the enslavement of Black people. On the days when there were no scheduled lectures, he would visit a daguerreotype studio to have his picture taken. He enlisted these images as another thrust of his campaign, offering the public a positive view of a Black person to oppose the negative caricatures that were commonplace in newspapers. His handsome portrait was a weapon against these malicious images, because his photographs were sold by, and distributed from, the studios he visited. With them, picture by picture, he slowly changed the public’s perception of an African-American. Frederick Douglass knew back in the 19th century that Black images mattered.

When Douglass had his pictures taken, rendering an image of a person was a democratic expression. For a small sum, the kitchen chemistry to sensitize a glass plate made it easy for anyone to have his or her image captured. Doing so became even easier as photography was adopted as an American pastime, and camera manufacturers not only produced film, but processed it. Taking pictures became a big business. And W.E.B. DuBois, an African-American scholar born about 50 years after Douglass, also had great hopes that it would serve the cause of racial justice. DuBois knew the power of displaying Black images to sway the American consciousness. And he used pictures to showcase his race’s achievements with material that included portraits of educated Black individuals, images he showed in his Exhibit of American Negroes at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris.

But unlike Douglass, DuBois grew leery of photography. Although it was a powerful way to push back against the stereotypes, this tool was starting to work against him. DuBois noticed that “the average white photographer does not know how to deal with colored skins,” he said. And the resulting pictures of Black people were often a “horrible botch.”

In 1915, as DuBois struggled with images of Black people, photography—and portrayals of African-Americans in particular—took a hideous turn. That year D. W. Griffith released his film The Birth of a Nation. This movie fabricated a false narrative of the Civil War and offered a redemptive account of the acts of the Ku Klux Klan: Griffith depicted the white supremacist secret society saving the nation from lecherous Black people (who were actually white actors in blackface). His film became the most loved movie in the nation. It was even watched in the White House by its fan in chief, President Woodrow Wilson. Griffith was a masterful moviemaker who pioneered the close-up, scenic long shot, and the crosscut. And he created a film that further contaminated the country. Griffith, like DuBois and Douglass, knew the power of pictures.

Negative portrayals of Black Americans took on a new force as, within a year after The Birth of a Nation, the Great Migration from the South to the North began. While many books will say that African-Americans came to the North for jobs, a truer reason was that they were fleeing for their lives. Terror was the law of the land, and lynchings were very common. For many of these murders, cameras were ringside, capturing burned and broken Black bodies. These photographs were often sold and distributed. Unlike Douglass’s portraits, they were not rendered to make African-Americans more human but less.

In this time, the U.S. was a hotbed of intimidation. As the number of lynchings increased, many spoke up against them, but their voices were largely ignored. The Herculean efforts of Black journalist Ida B. Wells, starting in the 1890s, brought these atrocities to the national attention. While Black people knew of them, what the mainstream world needed was proof. And Wells collected statistics of their occurrences and wrote up depictions of lynchings in her newspaper. Beginning in 1916, the NAACP picked up this work. It also found other means to make such murders a part of the public conversation: in the 1920s and 1930s, it flew a flag outside of its building stating, “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” Wells and the NAACP used technology to provide hard evidence, and they filled the national consciousness with images and newspaper articles and flagpole alerts in an effort to create change.

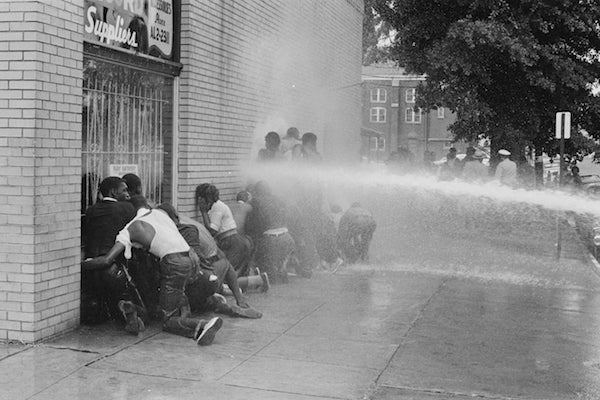

The flash point for that change came from a picture. Lynchings had long been an exertion of power by whites. Then a Black mother named Mamie Till redirected the use of photography as an attack, wielding it against the attackers. She did so by allowing photographs of the open casket of her lynched son, Emmett Till. It was the picture of his mangled and bloated 14–year-old body that catalyzed the civil rights movement. Other pictures, of a Black woman arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus in 1955, would be followed, in the 1960s, by film and video footage of young Black protesters hosed by water cannons. The whole world watched as this revolution was born. This younger generation of Black individuals was willing to push back against the oppressive system, unlike the generation before them, because they saw no other way. Years of images of Black people had not changed. They were aware that their own image was beautiful, much as Douglass had hoped, but this was the time to shift how they were viewed in the nation. And it was going to take putting their Black skin in front of harm—and the camera—to do so.

Today pictures from our digital cameras pervade our social media feeds—and our attention. The cameras embedded in our handy cell phones have made it possible for every occasion and amusement to be captured. Yet it was also this technology that helped to spark a racial justice movement. An array of NASA-designed photodetectors, smaller than a thumbnail, sat ready to dispatch an image across the Internet, making it possible for any event to be seen across the globe in real time. It was with a cell phone camera that the video footage of the killing of George Floyd, like a modern-day lynching, became a flash point, much like that of Till a few decades earlier. This time was different, however, because the whole world witnessed it. This time the whole world reacted. This time marchers, both Black and white, cried out that Black Lives Matter. The cell phone camera recorded the misuse of power but also displayed to the protestors that they have their own.

For generations, Black Americans have raised their voices about the atrocities against them, using the technology of the time. And one of the ways they displayed racism was by using their Black figure in front of cameras to bring it into better relief. Many allies today have said they were not aware of their privilege or their racism, likening both of them to water for fish. The detection is no longer a mystery, however. Pictures have long provided proof of anti-Black racism, first starting as occasional disturbances in the water in the days of Douglass to the torrent of them flooding our cell phones today. But cameras and their photodetectors can only do so much. They can only bear witness. Once something is seen, the next step is not just to say something but to strategize, to reimagine the future and, most importantly, to act.