With protesters in many American cities marching for justice, and with the Supreme Court delivering a historic ruling protecting gay and transgender workers from workplace discrimination, this summer is shaping up to be a watershed moment for equality in America. But while much of our national conversation is focused on urgent issues like police brutality, it’s time we acknowledged that American health care, too, is long overdue for a reckoning with systemic forms of discrimination that have a detrimental effect on the health and well-being of tens of millions of American women.

Take, for example, heart disease. It’s the leading cause of death among women—but a 2012 survey conducted by the American Heart Association (AHA) found that 44 percent of women were unaware of this, with the highest percentages of unawareness among Blacks and Latinas. Why this discrepancy? Why are so many women more concerned with, say, breast cancer than they are with heart disease, a condition that kills six times as many women each year?

The AHA has explored that question, too, and found that many women reported that their physicians seldom if ever talked to them about heart health, and, in some cases, misdiagnosed obvious symptoms of heart disease as panic, stress or even hypochondria.

That is a blatant example of how inherent biases put women’s lives at risk, but it’s not the only one. Gender, the socially constructed roles and behaviors associated with being male or female, is very much a part of the so-called “social determinants of health,” which researchers now believe play a large part in determining a patient’s well-being.

How do these factors—which include everything from poverty and literacy rates to social relations and expectations—affect men and women (including transgender individuals) and people of color differently? Why is one group more susceptible than another? The reasons include racist and sexist barriers embedded in our institutions and communities, whether we are aware of them or not.

We at Northwell Health have created our Center for Equity of Care that includes the division of Diversity, Inclusion and Health Literacy (DIHL), which establishes networkwide policies and procedures to ensure meaningful access to services, programs and activities to incorporate health literacy, language access and cultural competency as integral parts of the delivery of safe, quality patient-centered care. And at the Katz Institute for Women’s Health, we address decades of sex- and gender-based disparities in health and health care delivery through a new model: one based on unique clinical programs, sex- and gender-focused research and community partnerships. Many other health systems have similar programs to tackle these issues.

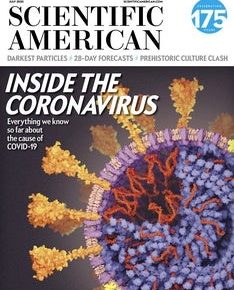

Preliminary data, for example, suggest that women have been more economically disadvantaged than men as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. That makes sense: Women are overrepresented in service-related jobs such as retail and hospitality, face higher risk of layoffs because of those jobs, and also tend to fill more marginal and lower-authority jobs.The closure of schools and day care centers has massively increased childcare needs, which has largely impacted working mothers. Gender-based domestic violence has increased as a result of heightened tensions in households at the same time that essential health support services are being disrupted or made inaccessible as a result of the need to socially isolate.

Gender also plays a role in the scientific study and management of the pandemic. Most alarmingly, women scientists are underrepresented among investigators studying COVID-19—presumably in part because women scientists and physicians also have to manage household issues like homeschooling their children—making it less likely that representative research questions are being asked. Preliminary data also suggest that countries with female leaders have been especially successful at managing the pandemic. We need more of these female leaders at the table to make decisions globally, whether it’s through the WHO or in talks with scientists working on vaccines.

When it comes to fighting disease and maintaining health, sex, gender and race matter. We need to design the right COVID-19 studies now to identify the reasons for the sex, gender and race disparities—and develop appropriate interventions. And we need to ensure that women, and communities of color are represented in designing and implementing solutions.

Equitable health outcomes and the health of our society depend on it.