Beau Bassin–Rose Hill, Mauritius—Nearly two weeks after the Japanese-owned, Panamanian-flagged ship MV Wakashio ran aground off the coast of Mauritius late last month—immediately destroying more than 600 yards of fragile coral reefs—the bulk carrier began leaking oil into the pristine blue lagoons of the Indian Ocean island. The spill threatened to do much greater damage than the ship itself.

Within hours of the leak, more than 5,000 local volunteers and dozens of career conservationists jumped into action to save their remote nation’s vibrant, unique wildlife by controlling the oil and moving some species out of harm’s way.

Like other isolated islands, Mauritius developed rich and diverse ecosystems. But starting about 400 years ago, successive Dutch, French and British settlements butchered the natural habitat, leaving only 2 percent of its native vegetation intact and killing off the famous dodo. Since winning independence from the U.K. more than 50 years ago, the nation has worked to restore its ecosystems. Mauritius has a high-income economy and a multicultural population, and it is one of the world’s most peaceful countries, renowned for its idyllic shores.

It is on these shores, near the picturesque coastal villages of Mahébourg and Pointe d’Esny, that volunteers gathered to build floating “sorbent booms” made of chains of stretch nets filled with dried sugarcane leaves that act as barriers that slow the oil’s spread. Research has shown that natural materials (such as dried sugarcane leaf or straw) are good at trapping oil in their matted, crisscrossed fibers. Additional volunteers gathered in shopping malls and public areas around the island to build the booms, deploying more than 400 yards of them near the wreck site in the Grand Port Lagoon, off the southeastern coast of the island.

Booms can only do so much, though—especially when buffeted by high waves and a strong current, which still spread much of the leaked oil. It quickly surrounded the lagoon’s majestic coral islet of Ile aux Aigrettes. The 67-acre island has been a nature reserve for decades, with 80 percent of its forests restored following the deforestation started by European colonists. It is a sanctuary for hundreds of birds, reptiles and plants that are threatened and found only in and around Mauritius.

Conservationists at the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF) had started preparing for the eventuality of spreading oil as soon as the ship ran aground, and they swiftly implemented a well-rehearsed plan to evacuate some of the animals and plants that were most at risk. “We had to relocate critically endangered species first, then we moved to endangered ones,” says Vikash Tatayah, MWF’s conservation director.

Within hours, teams had relocated 4,000 plants from 40 species, including the rare Aerva congesta, an endemic herb found on a mere 2,000 acres of the entire planet. This extraordinary rescue was only possible with the help of local laborers, who carried plants potted by MWF staff and evacuated them by boat. Conservationists hope to return most of the plants to Ile aux Aigrettes once it is safe to do so.

Relocating some of the islet’s rare birds was trickier. It took two days and six MWF staff, battling against toxic fumes from the oil spill, to catch 18 birds. “It’s a very slow process,” Tatayah says. “We use mist nets or catch them at food stations when they come to feed.” (The birds live in the wild, but conservationists had set up feeders to help supplement their diet as Ile aux Aigrettes is restored.)

Catching the birds and moving them to the main island is crucial to secure their populations in case the spill causes a catastrophic collapse in their numbers. Of the 18 birds the MWF staff caught, six were Mauritius fodies, a rare endemic species. Another 12 were Mauritius olive white-eyes, a critically endangered olive-gray bird that has characteristic white rims around its eyes and is no taller than the average human index finger. The Mauritius olive white-eye is also the nation’s rarest endemic bird; a 2016 thesis paper suggests it could go extinct within 50 years. But following extensive conservation efforts involving artificial egg incubation, feeding chicks from a menu that included bee larvae, scrambled eggs and papaya, and years of release and monitoring, 73 olive white-eyes were in the wild on the islet before the emergency evacuation.

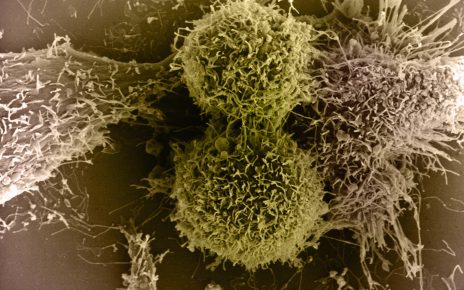

Just more than two weeks after the spill, with most of the more than 1,000 tons of oil that seeped into the sea removed, there is still considerable uncertainty about the extent of damage it will cause—particularly below the sea surface. Some fear the worst: Even before the spill, Pramod Kumar Chumun, an environmental scientist at a local nongovernmental conservation organization called Eco-Sud, and his team had recently been seeing more coral bleaching. They have documented a decrease in coral cover and diversity in specific areas of the Grand Port Lagoon. For more than two years the researchers have been growing corals from fragments broken off by boats and relocating them to some of those degraded areas. They were hoping to propagate 1,000 or so coral colonies, but the oil spill has forced them to pause, leaving budding corals in the nurseries to fend for themselves. “I’m not sure what’s going to happen to our coral nurseries,” Chumun says. “We couldn’t care for them during the [COVID-19] lockdown, and some died. This oil spill is not helping.”

Some past research on the effects of oil spills paints a gloomy picture overall. For example, a long-term assessment of impact on Caribbean Sea corals from a 1986 crude oil spill in Bahía Las Minas, Panama, found extensive mortality. Nearly all of the affected area’s branching corals were killed, and there was no evidence of recovery five years after the spill. Further, a team of U.S. researchers has found that exposure to oil impacts the developing hearts of larger predator fish, including tuna—which are plentiful in Mauritian waters—and also causes jaw defects, small eyes and other malformations.

But every oil spill is unique. There are many variables, such as the type and blend of oil involved. Marine ecosystems also have their own special complexities, so comparisons can be imperfect.

To get a better sense of the damage in Mauritius, “we need to survey the coast and go beyond the oil-spill zone to see if there are any changes to the region’s ecosystem,” says Jacqueline Sauzier, president of the Mauritius Marine Conservation Society. Only then will conservationists know what it will take to remedy the damage.