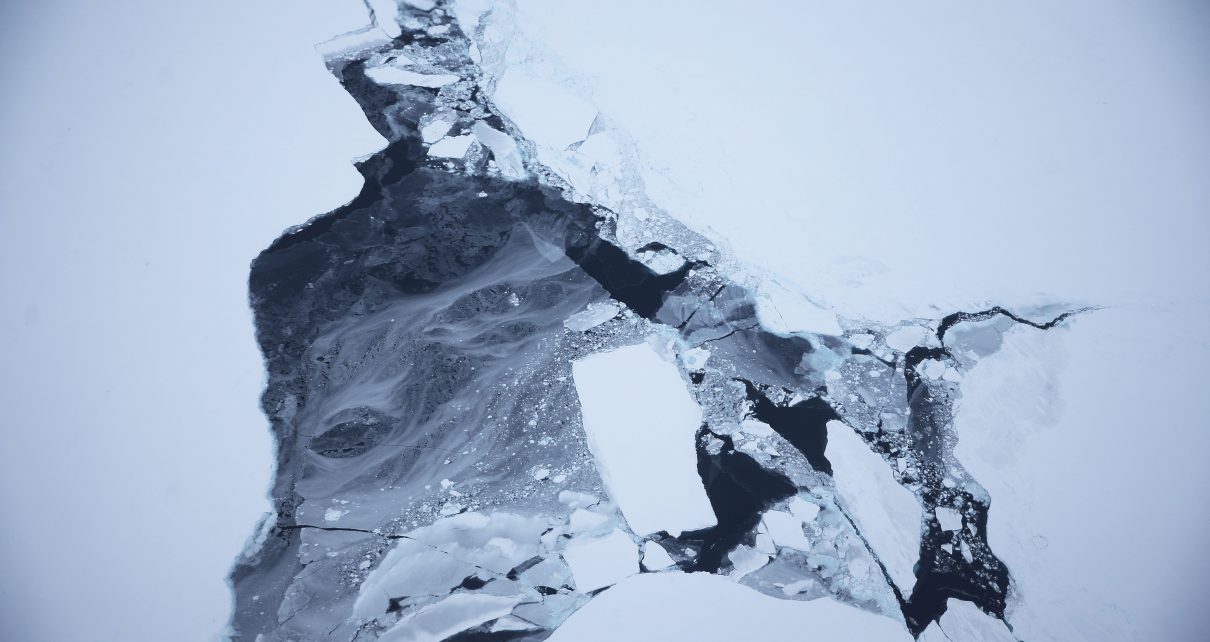

Antarctica’s Larsen B ice shelf—a large ledge of ice, jutting out from the edge of the continent into the ocean—captured international attention in 2002. Over the course of just a few weeks, the ice shelf splintered, broke into pieces and collapsed entirely into the sea.

Nearly 20 years later, it’s still one of the most dramatic events that scientists have observed in Antarctica.

But it may not be the last. New research suggests some of the same factors that caused the demise of Larsen B could threaten dozens of other ice shelves around the Antarctic coast.

It doesn’t mean they’re in immediate danger of collapse. But as the Southern Hemisphere warms—and the ice sheet melts at faster rates—the risk could be rising.

Scientists believe surface melting on the Antarctic ice sheet was a major contributor to the collapse of Larsen B. The process goes something like this: As the ice melts, liquid meltwater flows along the surface of the continent and seeps into cracks in the ice. The water then refreezes inside these cracks, expanding as it turns back into ice.

The expansion widens the cracks, putting more stress on the ice. Eventually, the pressure becomes too much and the ice splinters and breaks into pieces. In extreme situations, this process can cause entire ice shelves to disintegrate.

It’s a process known as “hydrofracturing.” And a new study, published yesterday in Nature, suggests that more than half of Antarctica’s ice shelves could be at risk.

The study takes a unique approach to the question.

The researchers, led by Ching-Yao Lai of Columbia University, trained a neural network—a kind of machine learning algorithm—to recognize fractures in Antarctic ice shelves on satellite images.

They used this information to determine where these kinds of cracks were most likely to form and which ice shelves might be at risk of crumbling if enough meltwater flowed across them.

The biggest concern about collapsing ice shelves is how they may affect the rest of the ice sheet. Many ice shelves help to stabilize the glaciers behind them. If they break apart, they can unleash an unstoppable deluge of ice into the ocean, contributing to global sea-level rise.

With that in mind, the researchers mapped out which vulnerable ice shelves are also key stabilizers of the ice sheet.

They found that about 60% of all the ice shelves around Antarctica meet both criteria: They’re holding back large volumes of ice behind them, and they’re potentially vulnerable to hydrofracture.

The study doesn’t suggest they’re in danger of collapse any time soon. Hydrofracturing doesn’t happen until enough liquid water is flowing over the top of the ice.

But it warns that enough future melting could put them at risk.

For now, most of the ice loss in Antarctica is happening from the bottom up, not the top down. Warm ocean waters are lapping against glaciers at the edge of the continent, seeping underneath the ice shelves and thinning them from below.

But as the climate continues to warm, more melting may happen on the surface of the ice sheet.

The new study doesn’t include any estimates on how soon these ice shelves may be at risk.

Still, it highlights the locations that scientists should keep an eye on, according to Jeremy Bassis, a scientist at the University of Michigan.

In published commentary on the new research, he noted the findings “show that large sections that are currently stable could collapse as atmospheric temperatures continue to rise.”

And the combination of warming ocean waters and rising atmospheric temperatures could be a dangerous pair, he added. Antarctic ice shelves may increasingly be at risk of a double whammy: simultaneous weakening of the top and bottom.

A “deeper understanding of the effects of both the ocean and the atmosphere is needed to accurately predict the fate of ice shelves in a warming climate,” he wrote, “because ice shelves are vulnerable to attack from above and below.”

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from E&E News. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net.