Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom. —Apocyphal, often attributed to psychiatrist Viktor Frankl

“We need to learn to live with it.” That, essentially, is the current response being put forward by the United States government and many state governments, as COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, continues to wreak devastation around the country. At the time of this writing, the U.S. has over six million cases of COVID-19, with over 180,000 deaths.

My institution, the University of Michigan, and my state, had a relatively successful response to COVID-19. Our medical center’s incident command center was opened on January 24, within days of the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the U.S. Our Regional Infectious Containment Unit (RICU), a unit specially designed for highly transmissible infectious diseases, opened within five days of the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the state on March 10. This rapid mobilization saved lives, and allowed even the sickest with COVID-19 a fighting chance. After peaking at close to 250 inpatients (about 25 percent of our total hospital capacity) battling COVID-19 in April, our numbers rapidly declined by the beginning of June. However, these numbers don’t tell the whole story.

The direct losses nationally from COVID-19—over 180,000 mothers, fathers, grandparents, sisters, brothers, children and friends gone—are devastating. Those who died from the virus and their families are not the only ones to suffer from the poor national response to the pandemic, though. We are now seeing the second wave of death and morbidity in our hospital—but not from COVID-19 itself, where our case numbers have been in the single digits to low teens for several months. This next wave of is from delayed care because of the prolonged effects of the virus on our troubled health care system.

COVID-19 is currently the third leading cause of death in the U.S. But that means there are two scourges that are still causing even more morbidity and mortality: heart disease (the number one killer in America) and cancer (number two). Over the summer, in my work as a hospital-based geriatrician, I have managed multiple deaths from end-stage heart failure, and made several new cancer diagnoses in more advanced stages of disease with limited treatment options. The amount of death and suffering I’ve witnessed this summer, not having worked directly with COVID-19 patients in months, is amongst the worst I’ve seen in my entire medical career.

A Washington Post investigation found that there were 8,300 more deaths from heart disease in five states (New York, led by hard-hit New York City; Massachusetts; New Jersey; Michigan; and Illinois) between March and May, about 27 percent higher than would be predicted from previous years. New York City alone saw more than 4,700 excess deaths from heart disease. As hospitals in New York City were overwhelmed with COVID-19, they were unable to care for anyone else. This included people suffering from heart failure, complications of cancer or possibly undiagnosed cancer, and other conditions. There were simply no hospital beds in the entire city.

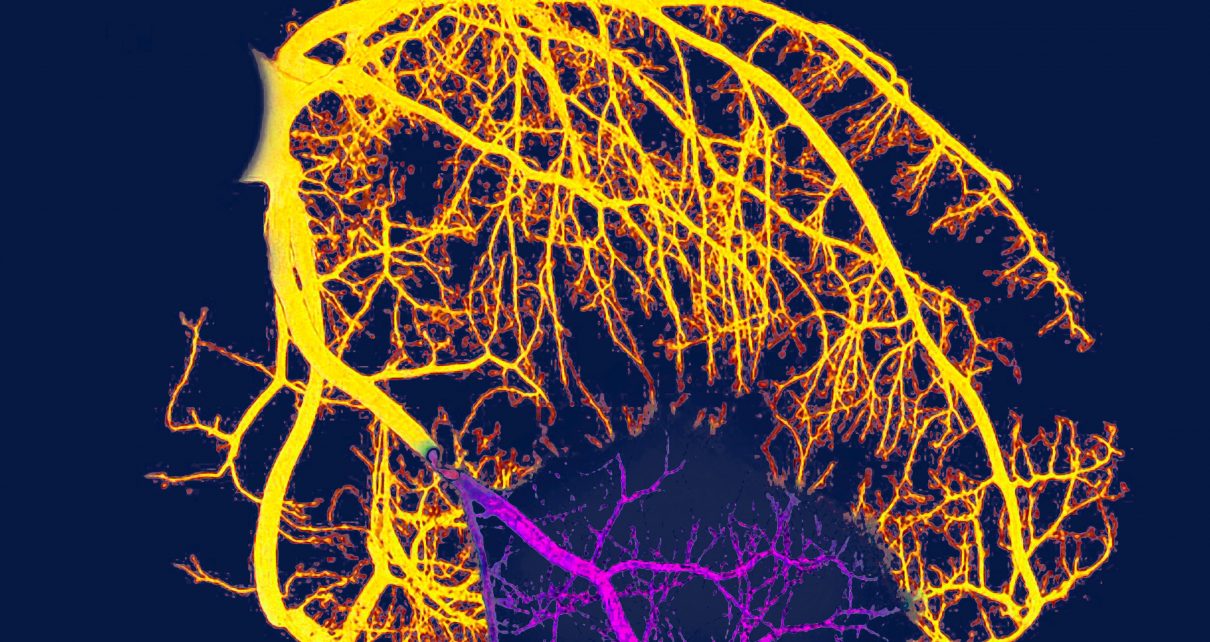

While cancer treatment is often managed outpatient, the initial diagnosis of cancer is often made in a hospital—either in the emergency department or on the hospital floor. When there are no available hospital beds, the investigation of vague symptoms of malaise, weight loss and unexplained bleeding is delayed; and cancer cells or tumors continue to grow unabated. For heart disease, people in chest pain may suffer in silence. The plaque continues to build up, until a condition that could be managed with a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a coronary catheterization with stent placement to hold the artery open, rapidly becomes a fully blocked artery that requires a completely new set of collateral arteries to keep the heart alive (coronary artery bypass graft, a far riskier surgery with longer hospital length of stay); or, even worse, something completely inoperable, causing inevitable death.

This betrays one of the greatest dangers of our 21st-century American health care system: the very low margins within hospitals. Empty hospital beds don’t make money. When medical care is monetized, the effect is closure of low-income hospitals, such as Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia in 2019, and hundreds of low-income urban or rural hospitals across the country. Even prior to COVID-19, many hospitals were running on razor-thin margins. We would get nearly daily e-mails that bed capacity was full, that dozens of patients were being housed in the emergency department for hours to days.

COVID-19 preyed upon an already broken system. Those hours in the waiting room, days in an emergency department awaiting a bed on the floor, have stretched into weeks or months without care. When we did not have available hospital beds anywhere in a region or state, when we hired only the bare minimum level of trained staff to “maintain profits,” we had no elasticity for handling a mass disaster, such as a pandemic. COVID-19 literally forced us to make decisions about whose lives are more important—those suffering from the virus, or those with other serious chronic illnesses? America’s health care system is like a diseased lung: it has no elasticity, no compliance, no room to expand such that it can take in enough oxygen to help it breathe.

At my institution, we were fortunate enough, through quick action both at the institutional level and at the state level from Governor Gretchen Whitmer, that we still had enough hospital beds even in the peak of our pandemic to help the sickest people without COVID-19; ventilators for those with cancer or severe heart failure, to buy us time to possibly save their lives, or at least have meaningful goals of care conversations and an orderly transition to hospice and returning the critically ill person home. Many cities and states have not been so lucky.

What many fail to realize is that if the United States had a rapid, organized pandemic response on a national level, this not only would have saved tens of thousands of lives from the COVID-19 virus itself, but also would have given people with serious chronic conditions, including heart disease and cancer, a better chance of getting the treatment they need for survival. For those with unsurvivable disease, this would have given them a hospital bed, a goals-of-care conversation including the patient and their loved ones, and the time they needed to manage their death on their own terms.

When the pandemic is over, it will be clear that the hundreds of thousands of deaths from COVID-19 will be just the tip of the iceberg. In the space we were given between stimulus and response, collectively America did nothing, and instead of growth and freedom, we will have witnessed the suffering and death of millions of Americans. However, another space has now opened up: Is an empty hospital bed $3,000 in profit lost that day, or instead a place available to provide lifesaving care to a person in need? We have the power to choose our response at the ballot box.