The CDC’s Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report, familiarly known as the MMWR, has been around for nearly a century, and is sacrosanct in the public health community. Loaded with reliable, timely data and analyses and authored by the world’s top scientists, it is required reading, especially during a pandemic.

To meddle with, delay or politicize these reports would be a form of scientific blasphemy as well as a breach of public trust that could undermine the nation’s efforts to fight the coronavirus. If public health officials lose confidence in this vital tool and doubt the substance of these reports, the U.S. response to the coronavirus pandemic will have been dealt yet another setback that stands to play out with greater suffering and more deaths in communities across the country.

A report in Politico this past weekend suggests that communications officials at the Department of Health and Human Services have been pushing back on, altering and even delaying MMWR reports to better align with a political narrative about the pandemic. E-mails cited by Politico reveal tensions and pushback between political appointees and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scientists.

As acting director of the CDC at the dawn of the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, I felt the natural tensions that can occur between political appointees and career public health officials at CDC. During my tenure, the science was always—without exception—the driving force in the review process and in our communications to the public. Indeed, in the many decades I’ve spent in public health, including 13 years at CDC, science has been the arbiter of truth and carried the day no matter the administration or the political party. That must remain the case today.

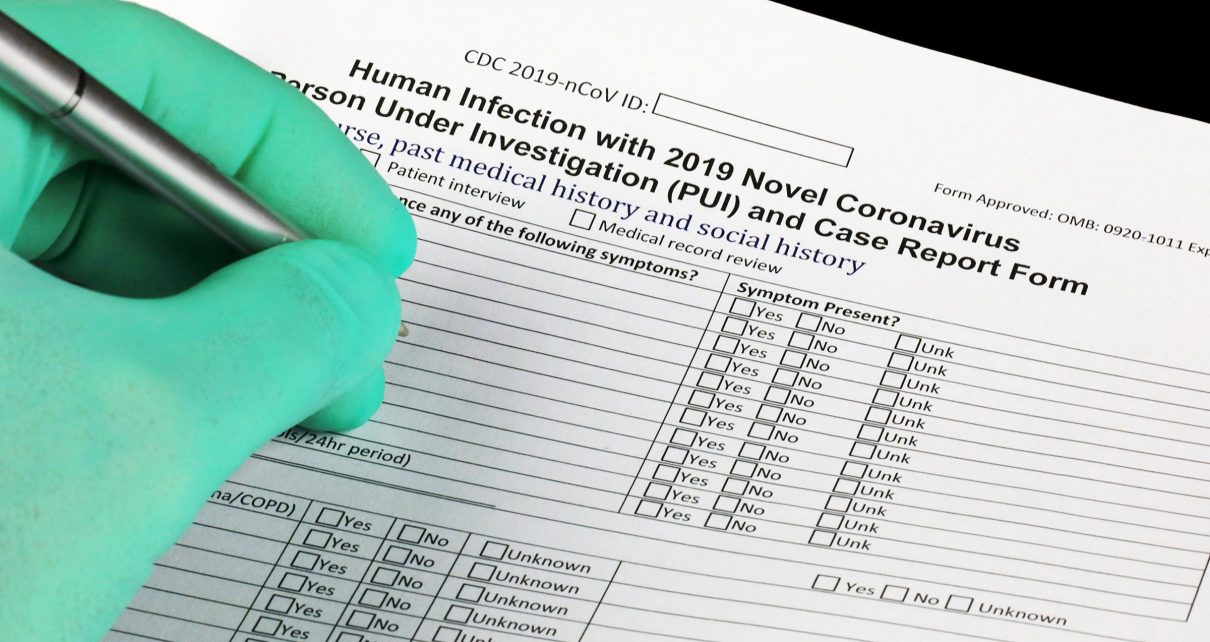

The MMWR is among the most sober and least political public health communiques one can imagine. The name itself—Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report—could only have been conceived by scientists rather than professional communicators. I’ve reviewed hundreds and co-authored several of these reports, which are notoriously meticulous, built on foundations of data and notably devoid of adjectives. The just-the-facts approach could be frustrating, in fact, because any public health guidance that carried even a whiff of the subjective would be expunged from the reports by science-driven editors. This is as it should be for public health communications written for the public health community, and it’s why the integrity of these reports has been second to none.

In 2009, the first communications from CDC about H1N1 were included in the MMWR. Two cases in California detailed in an MMWR in April of that year gave us an early indication that the virus first reported in Mexico had crossed into the United States. From that point forward—much as we’re seeing today—the MMWRs would serve as a valuable tool in filling in the gaps in knowledge while informing public health officials in every state in the country, and in real time, what they might be facing. These reports are the keepers of the latest statistics and allow for sharing of information to be used in planning and response during a public health crisis.

Because the voice of the CDC has largely been silenced during the coronavirus pandemic and unable to regularly reach the public, the MMWRs have become an even more critical conduit for the latest information and data. Produced like clockwork and driven by scientific rigor, they have detailed everything from COVID-19 spread at church events to outbreaks among college students to a comprehensive look at who is dying from COVID-19 in the U.S. The latest report, issued the day the Politico story broke, detailed COVID-19 outbreaks at three Utah childcare facilities. Each report is an important puzzle piece in helping on-the-ground public health officials better understand the virus and emerging epidemiological learnings.

Since the early weeks of this pandemic, there have been questions about political influence on the science and public health guidelines, and whether the CDC has been able to do the necessary work to inform and lead the federal government’s response. But even as these debates have raged about whether to mask or not to mask and whether hydroxychloroquine was or wasn’t an effective treatment for COVID-19, the MMWRs have continued to produce revelatory and relevant pandemic intelligence—scientific documents that appeared immune to the day’s politics.

Instead, we now see the undermining of the public’s trust of our key institutions at the very moment we should be shoring up that trust. In communities of color, in particular, that have been disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus, many already don’t trust government’s role in health and in their lives. Systemic racism has caused, and continues to cause, great harm in these communities. We know from this pandemic’s short history—and from MMWRs—that Black, Latinx and Native Americans have been bearing the pandemic’s greatest toll. As we head into fall and the very real possibility that a coronavirus vaccine will be approved for public distribution, we cannot afford any further disintegration of trust in these communities and beyond. After all, a vaccine only matters if the public at large gets vaccinated.

The landmark of 200,000 deaths that is fast approaching reflects a scale of tragedy that the United States did not have to bear. CDC science should not be undermined nor the voices of its experts muted, or our nation will suffer a crisis of confidence and trust that will continue to hamper our recovery from this pandemic and open the door for more death and more suffering.

We cannot let this happen.