DENVER—A weather drama is playing out in the forests of north-central Colorado as two record wildfires—supercharged as the result of climate change—meet the first large snowstorm of the winter.

One possible outcome is that the snowstorm dampens the two fires so the 3,500 firefighters struggling to contain them can protect surrounding areas.

Another is that the snow does little to help and the two fires merge in Rocky Mountain National Park and create a megafire in one of the West’s most popular recreational areas.

The two record fires—each much larger than the area of Chicago—broke out after a third fire already had set a state record this summer for acres turned into ashes.

“We’re really rewriting the record book in terms of fires this year,” said Russ Schumacher, Colorado’s state climatologist, in an interview. “If anyone would have asked last week, we would have said it’s a very extreme fire season, but what’s happened in the last few days has taken it to another level.”

The first shock came late Wednesday when a small wildfire called East Troublesome expanded by more than 100,000 acres overnight. Schumacher and other experts refer to it as an “explosion” they had never seen before.

It sent deputy sheriffs sprinting from door to door in Granby, Grand Lake, Estes Park and other small towns in the area, warning people that they needed to evacuate immediately. Streets were soon jammed with cars. Thousands of people were finding their way out of town in the smoky darkness.

Most of them were lucky. But not all. An elderly couple died after refusing to leave their home in Grand Lake. Firefighters and local officials were still adding up the damage, but one of them told The Denver Post that “a lot” of homes have been destroyed. Climate experts like Schumacher are trying to piece together exactly how the “explosion” happened, but he says the likely causes have come together over the last three years.

East Troublesome, like most wildfires, got its name from the geographic point where it started. It is the name of a creek in the Arapaho National Forest that frequently overflowed—much to the ire of railroad companies that saw their tracks washed out.

What baffled everyone was how quickly the wildfire managed to live up to its name, enlarging from 30,000 acres to 160,000 acres over two days. “I don’t think we’ve ever seen that before,” said Larry Helmerick, spokesman for the Rocky Mountain Area Coordination Center, which helps direct firefighting efforts of the federal government and agencies in Colorado and four nearby states.

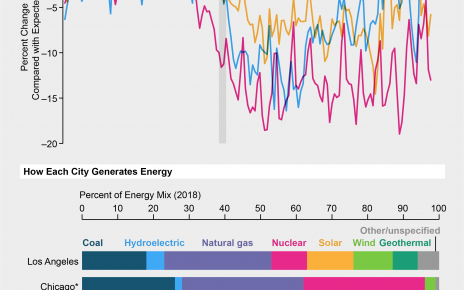

When the snow began yesterday morning, East Troublesome, by then 192,560 acres and only 10% contained, was in danger of merging with its larger neighbor, the Cameron Peak Fire, which was scorching a 208,663-acre swath of forests and mountains near Fort Collins. (As a point of reference, the city of Chicago covers 149,760 acres.)

Rocky Mountain National Park was closed last week after East Troublesome neared it. Now the question is whether 10 to 20 inches of predicted snow can help protect it.

By any measure, the sizes of Colorado’s new fires are stunning compared with those of fires in the past. During the 1980s, according to Colorado data, a record-setting blaze was one that destroyed 15,000 acres.

According to the office of Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D), 90% of the two new fires are burning in national forests and other federal land. They are both suspected of having human causes, rather than lightning.

In a news conference Friday near the fire area, Polis attributed the size of the fires to a “hotter, drier climate.” That squared with estimates by Schumacher and another climate change expert, Philip Higuera, an associate professor who teaches fire ecology at the University of Montana.

Schumacher noted that Colorado traditionally enjoyed relatively cool summers, followed by fall rains brought by the North American monsoon. “In the last three years, we’ve had basically no monsoon rainfall,” he said in an interview.

Meanwhile, the summers have become unusually hot, especially this year, with temperatures reaching 90 and 100 degrees Fahrenheit in Colorado cities. That kind of heat, he pointed out, is closer to normal for California, a state that has had 17 large wildfires this year.

Higuera agreed that the combination of high heat and increasing drought set the stage for Colorado’s spate of record-setting fires since July. That makes forests and grasslands “extremely sensitive to ignition,” he said, adding that “once the fire starts, it spreads more rapidly.”

Colorado fires usually come in August. But the most recent fires arrived in late September and mid-October, a time when Colorado can have 60 mph winds, which troubled the firefighters last week. “When you add that, it’s kind of like putting a blow-dryer on the fire,” he explained.

“I hope this year catalyzes change in both federal policy and state land management,” Higuera added. “They’re a wake-up call telling us that the way we’re living with fire is not working.”

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from E&E News. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net.