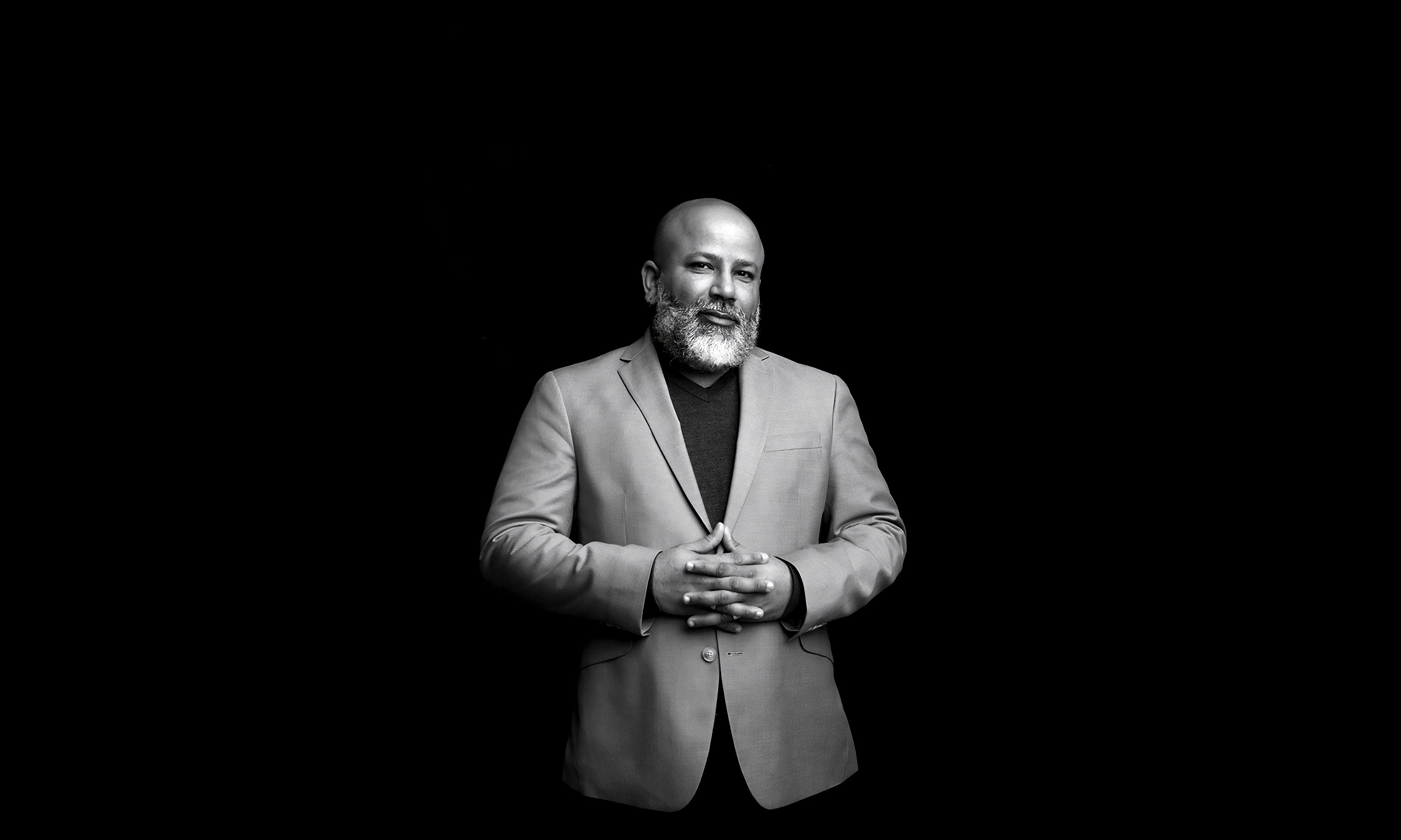

“When you’re dealing with an institutional structure like global science, one of its core features is that it has been a racial structure,” says sociologist Anthony Ryan Hatch, an associate professor and chair of the Science in Society Program at Wesleyan University. “To dismantle and chip away at that system requires concerted effort, concerted resources, clear thinking, and a concern for equity and making things right.”

But Hatch believes that even the effort to diversify institutions of higher learning, in terms of students and administration, has a potentially fraught set of challenges:

These structures are very resistant to change. And they are difficult to challenge, because in some cases, it involves directly not just calling out individual gatekeepers (key faculty members or deans or university heads or center heads) who are making biased decisions and who are letting assumptions about the excellence of, say, a candidate, the perceived excellence or lack thereof…, determine who gets a job—basically, just being racist. It’s one thing to think about the individual people you might need to challenge, but when a structure produces these kinds of racial patterns, it’s so much more challenging to intervene.

Hatch works and lives at the intersection of several fields: health, the environment, criminal justice and medicine. He says he was able to access that many disciplines through a combination of the “empathy and grace” he was shown as a student and a series of mentoring programs for students of color.

Those experiences helped Hatch navigate the predominately white institutions he was attending. “I never felt that I was cast out to sea—that I didn’t have a support network to help me with my research, to help me improve my teaching, to help me pursue funding opportunities for my work,” he says.

Hatch began his academic career in community-based public health research at Emory University, where he worked on projects related to drug use, HIV/AIDS and mental health. He is the author of Silent Cell: The Secret Drugging of Captive America and Blood Sugar: Racial Pharmacology and Food Justice in Black America. He has also held training fellowships at the American Sociological Association, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Science Foundation, and was a faculty fellow at Wesleyan’s Center for the Humanities.

Hatch knows that he was lucky. And he also knows that his success—and that of other researchers of color like him—does not mean that the work is done or that apparent progress is always true progress.

“I think that we’re at a very interesting moment, and it’s one that’s filled with tension or contradiction,” he says. “On one hand, you have a small class of well-trained scientists of color, and they have, through struggle and through sacrifice and through being positioned in the right networks…, risen to positions of power. And they’re highly visible. And in their visibility, they become both target and object to be consumed.”

Hatch says that to make real and lasting progress on diversity in science, one must look past that objectification. “One thing … that is needed,” he says, “is for people to have a good, clear-eyed sense of that distinction between the representation, the image of diversity—the image that we fixed the problem—and looking carefully at the structural reality.”

In this interview, Hatch discusses his thoughts on the hierarchy in STEM, the importance of mentorship from his experiences and his favorite innovator: Henry “Box” Brown.

Click here to watch an extended version of the interview.

This discussion is part of a speaker series hosted by the Black Employee Network at Springer Nature, the publisher of Scientific American. The series aims to highlight Black contributions to STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics)—a history that has not been widely recognized. It will cover career paths, role models and mentorship, and diversity in STEM.