World leaders moved forward this week with a global framework to stem the loss of biodiversity, but missing from the conversation was a critical potential partner—the United States.

For three decades, the United States has failed to ratify the Convention on Biological Diversity, a global treaty to tackle threats to the world’s plants, animals and ecosystems. That stance forced the United States to the sidelines this week as diplomats and delegates gathered in Kunming, China, to discuss the deal.

Washington’s obstinance is striking. The United States has stayed out even as the rest of the world has signed on—including U.S. geopolitical rivals such as China and Russia.

It is not without consequence either. Because the United States has refused to ratify the Convention on Biological Diversity, it cannot vote on procedures that continue to shape the treaty. And critics say the lack of participation in this arena hurts U.S. diplomacy in other environmental matters, such as global warming.

“It reinforces the notion that the U.S. is a fair-weather partner when it comes to environmental conservation, including issues of climate change,” said Stewart Patrick, a senior fellow in global governance at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Nearly all the blame lies with the U.S. Senate, which for years has balked at approving the treaty. But the Biden administration hasn’t spent much political capital on it either—in a year that officials often describe as pivotal for the climate.

For decades, Republican lawmakers have argued against ratification because they say it would require that the United States bring its laws and regulations into conformity with global standards and infringe upon U.S. sovereignty. In addition, American industry groups have raised concerns that entry into the deal would pose a risk to intellectual property rights.

Patrick, of the Council on Foreign Relations, pushed back on both those arguments.

“It doesn’t oblige the U.S. to do anything it’s not already doing,” he said. And U.S. environmental protections tend to be among the world’s most rigorous, he added.

Paris Agreement for nature

Conservationists sometimes refer to the Convention on Biological Diversity as the Paris Agreement for nature, though it receives far less attention than the landmark climate pact, in part because the two issues are often conflated.

It’s designed to protect global biodiversity and share its benefits equitably, a nod to the genetic resources that go into medicines and other nature-based goods.

The United States worked to bring it to life during the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, when George H.W. Bush was in office. But opposition in the Senate has kept the U.S. from becoming a party to the convention.

As an observer, the United States can send a delegation to the conference in Kunming and make statements, but it can’t vote on updates. A spokesperson for the State Department confirmed the United States would participate virtually.

Patrick sees that as a missed opportunity for the United States to help shape the next round of targets under the convention.

At yesterday’s meeting, other global leaders committed to guidelines for a new 10-year framework for the Convention on Biological Diversity that would focus on more robust, achievable measure to protect and restore nature.

The declaration calls for phasing out and redirecting harmful subsidies, hardening the rule of law, recognizing the role of Indigenous peoples, and devising a mechanism to monitor and review progress toward protection efforts. That framework is slated for adoption at its conference next May.

Major hurdles remain. A U.N. report released last year found that none of the previous 10-year targets set in 2010 had been fully achieved.

Much of that owes to a lack of funding needed to meet those objectives, as well as the fact that many nations have taken a more domestic than global approach to the targets.

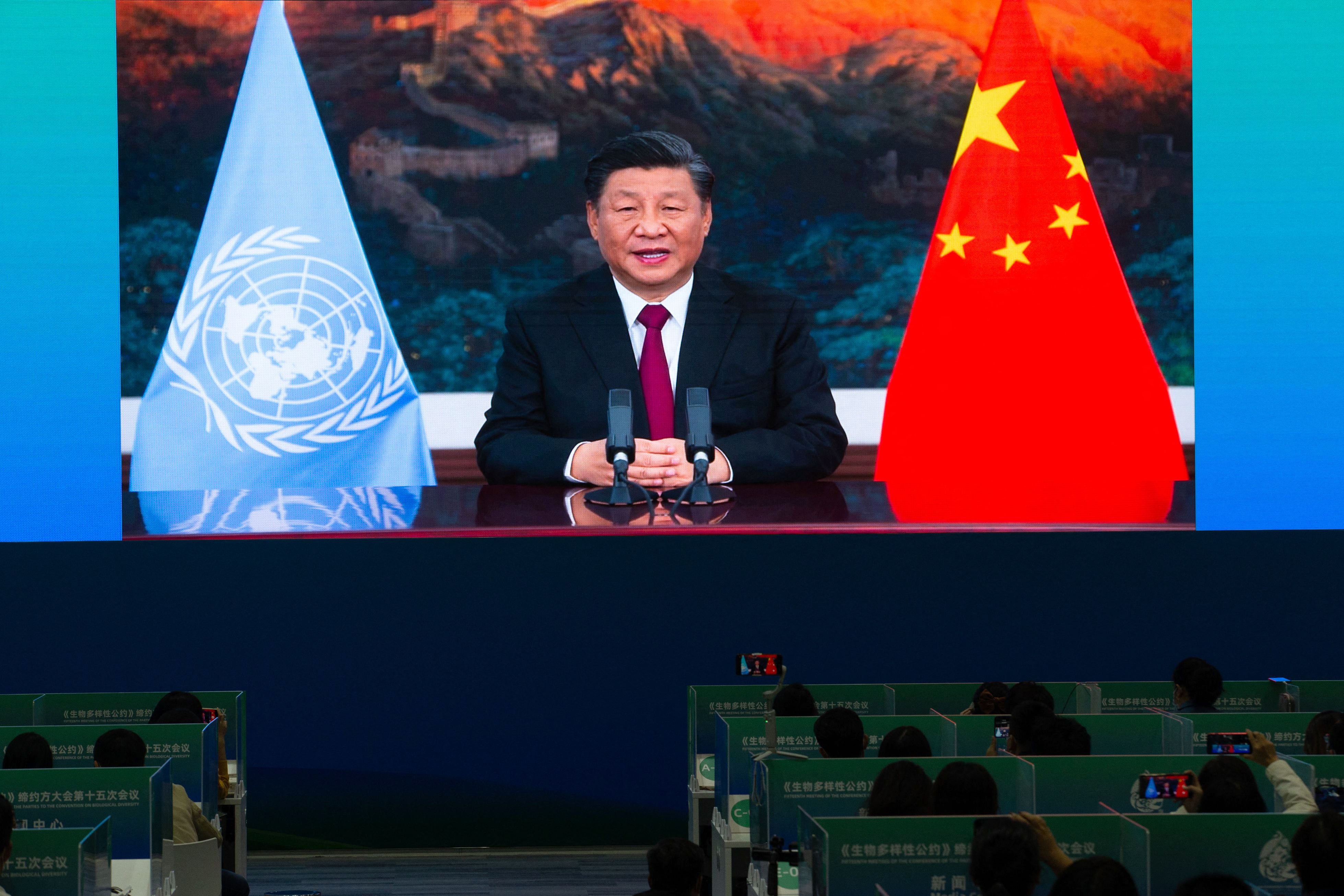

The meeting comes just weeks before global talks on climate change are set to kick off in Glasgow, Scotland. In the run-up, the U.S. and other leaders have been pushing China to more quickly ratchet down its planet-warming emissions and commit to phasing out coal, its primary source of energy. On biodiversity, however, China has stepped out in front as the current host of the convention.

At the opening of the meeting this week, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged $230 million for a fund to support biodiversity protection in developing countries and highlighted the country’s work to expand its national park system (Greenwire, Oct. 12).

For its part, the United States has made some progress domestically in trying to safeguard biodiversity.

The Biden administration has endorsed a proposal to protect 30 percent of national lands and waters by 2030. That 30×30 goal is expected to be a centerpiece of the new Convention on Biological Diversity framework.

America also has signed onto a communiqué among the Group of Seven that calls attention to the importance of biodiversity.

A spokesperson for the State Department said the United States strongly supports the objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity and is committed to tackling the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Still, the convention remains before the U.S. Senate for ratification, and Patrick says he’s seen little movement to pick it up.

In the meantime, the United States could join other international efforts outside the Convention on Biological Diversity, said Brian O’Donnell, director of the Campaign for Nature. That includes the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, which supports the 30×30 goal.

This kind of low-hanging fruit would help the United States show leadership on nature, he said.

As for the divide between China and the United States, on one hand climate and nature could be one area for cooperation. Or it could prevent greater progress on what’s needed for the planet.

“The world cannot afford for China and the U.S. to not find ways to work together to address climate change and nature loss,” O’Donnell said. “Our survival requires it.”

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2021. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.