The fossilization process is an unrelenting slog of decay, compression and erosion that can take millions of years and favors the preservation of tough material such as bones, teeth and shells. But with a little bit of sticky tree resin and a lot of luck, delicate bits of plants and tiny critters can sometimes last for tens of millions of years. As the resin petrifies and turns into amber, it preserves whatever gets stuck inside of it—including insects, slime molds and even pint-sized dinosaurs—in a gold-tinted time capsule.

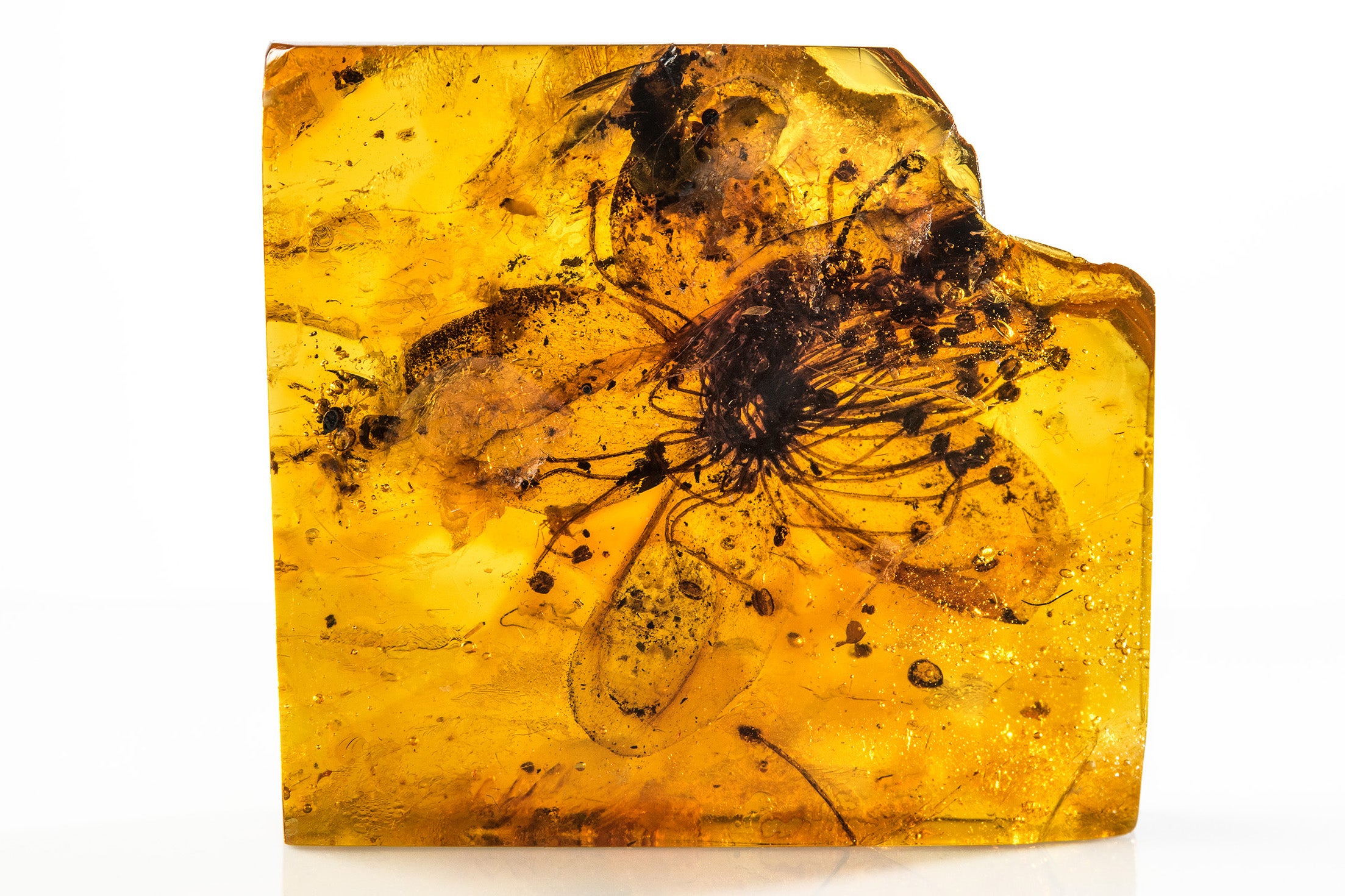

A team of researchers recently rediscovered one particularly stunning amber inclusion stashed away in overlooked museum collections for 150 years: a nearly 40-million-year-old fossilized flower. This tawny blossom, which looks like it was just plucked out of a bouquet, is the largest flower ever found in amber, the team reported on Thursday in a new study published in Scientific Reports. The blossom is so well preserved that the researchers were able to identify its floral descendants now residing a continent away.

The stunning find comes from the region around the Baltic Sea, one of the world’s premier amber hotspots thanks to the vast forests of resin-seeping conifers that once covered the area. During the late Eocene epoch, between 38 million and 34 million years ago, a glob of tacky resin oozed out of one of these trees and dripped down, ensnaring the flower.

At just more than an inch across, the fossilized flower may not sound particularly large. But it is about three times the size of most other amber-preserved flowers and larger than nearly half of all other Baltic amber pieces. According to study co-author Eva-Maria Sadowski, a paleobotanist at Berlin’s Museum of Natural History–Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, large flowers are rarely found in amber because it would take an incredibly large outpouring of resin to encase the entire blossom. “If you found a singular flower, they are usually quite small,” she says.

The newly reported fossil was uncovered sometime in the 19th century, when scientists scoured local mines and coastlines for amber. The flower, originally named Stewartia kowalewskii in 1872, was put in a glass case filled with modern tree resin—and then largely forgotten. According to George Poinar Jr., an Oregon State University entomologist, who specializes in studying insects and plants entombed in amber, the flower’s mere existence today is noteworthy. “There were many flowers described back then, but most were lost to science during the [World] Wars,” says Poinar, who was not involved in the new study.

Sadowski says a retired colleague tipped her off that one of the amber specimens in the collection of the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Germany contained a strikingly large flower. Sadowski immediately knew it was something special, and she jumped at the opportunity to reexamine one of these historical specimens with cutting-edge technology. The flower’s fragile reproductive organs were so well preserved that her team was able to extract intact grains of pollen with a scalpel. Under a scanning electron microscope, the pollen grains—which resembled inflated arrowheads—were reminiscent of pollen from tiny trees and shrubs in Asia that belong to the genus Symplocos. Today these evergreen trees are found in humid, high-altitude forests and produce yellow or white blossoms.

To reflect the entombed flower’s newly uncovered identity, the researchers have proposed it be renamed Symplocos kowalewskii, making it the first record of an ancient Symplocos plant preserved in Baltic amber. Basing their conclusions on this tree’s modern relatives, the researchers believe it would have been right at home among the sappy conifers in the warm climate that the Baltic region experienced during the Eocene. Sadowski thinks each new plant helps bring this ancient forest into focus. “I see each specimen as a piece of the puzzle to gain more knowledge about the whole forest,” she says.