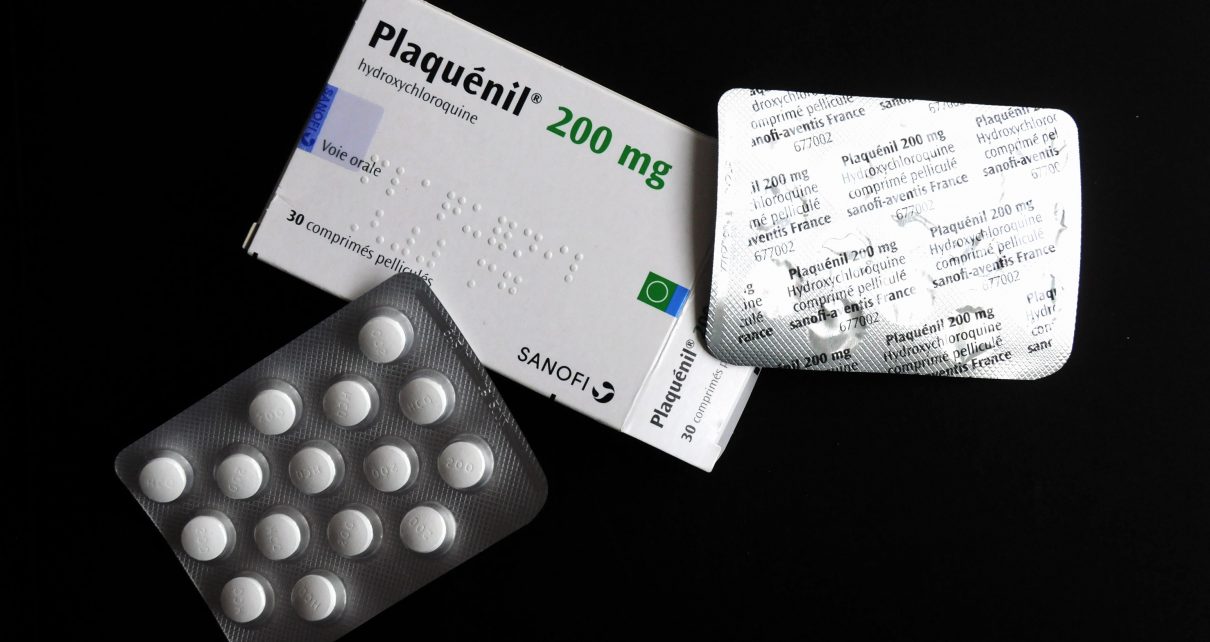

The recent announcement that the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved the “compassionate use” of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to treat patients with coronavirus disease has been received with mixed emotions around the globe. While many have hailed this move as a welcome development in the search for therapeutics against the COVID-19 pandemic, some find the news concerning.

Chloroquine is a synthetic drug introduced in the 1940s. It is a member of an important series of chemically related agents known as quinoline derivatives. Hydroxychloroquine is a related compound that was introduced in 1955. Both drugs are used in the treatment of tropical diseases such as malaria and amebiasis. But they are also useful in the treatment of various skin conditions and diseases of the joints such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. This is the source of apprehension among doctors working in developing economies.

Lupus is an autoimmune disease that can affect almost any organ of the body. Despite affecting four times more people of African descent than it does Caucasians, lupus is grossly underdiagnosed amongst Africans. This is likely because something called the prevalence gradient theory previously suggested that lupus occurrence progressively increased as one moved away from equatorial Africa. It held that lupus was practically nonexistent in Africa.

Apart from poor awareness and underdiagnosis on the African continent, environmental factors such as vitamin D deficiency in the West were hypothesized to explain this apparent paradox. The immune response to endemic infections as well as the widespread use of chloroquine for malaria treatment could be protective against autoimmune diseases. Improved knowledge regarding the diagnosis of lupus and other autoimmune conditions in sub-Saharan Africa has upturned the prevalence gradient theory. However, many cases remain undiagnosed because of the dearth of rheumatologists in the region.

Similarly, very little attention is being given to lupus among African children. This may be particularly true in Nigeria. Pediatric lupus represents 10–20 percent of all cases and is associated with higher disease severity, greater organ damage and increased overall mortality. Unfortunately, the recent lupus criteria published in 2019, while meant to improve diagnosis and early, treatment could lead to underdiagnosis in less-developed settings where the baseline antibody screening test is unavailable or too expensive.

Kidney failure is a feared complication of globally common diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. Other diseases such as HIV and lupus frequently affect the kidneys. Overall, kidney failure is known to be more severe in people of African origin. Among children, lupus-associated kidney disease affects 20–80 percent of patients with juvenile-onset lupus and 10–50 percent progress to end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis.

The double tragedy of lupus and kidney failure is not just a concern given higher mortality, but with regards to increased morbidity and treatment costs. Available data indicate that the mean annual direct costs of lupus treatment range from $13,735–20,926 per patient in the United States, $4,232 in the United Kingdom and $9,279 in Japan. Similar estimates for Africa are largely unavailable, and although they are projected to be lower, treatment remains out of reach for most patients.

In addition to the significant economic burden, the misfortune of lupus is unique in the fact that it mainly affects women in their reproductive years—the women who are the core of their families. Among South African lupus patients, pain, fatigue and aesthetic concerns negatively affect mental capacity, social functioning, job acquisition and sexual health. These facts create important challenges for families.

The strain on marital relationships is enormous, as sick patients are unable to care for their spouses and children. There is also the added difficulty of choices such as organ donation for loved ones with kidney failure. Bearing in mind that first degree relatives have up to 10 times higher risk of the disease compared to the general population, so transplant decisions become not only risky but potentially life-altering.

As the coronavirus pandemic rages on and the world battles to curb it, there is a deep sense of anxiety among doctors and lupus patients alike. COVID-19 poses a new occupational hazard to doctors, while lupus patients are at higher risk because of their weakened immune system. Beyond these, there is also growing concern that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, which have been relatively cheap treatments for lupus and malaria, will soon become unavailable because these drugs are being hoarded or diverted to treat COVID-19 patients in the developed world.

Early diagnosis and prompt commencement of lupus treatment remain the best way to prevent complications like kidney failure. Improved access to care and increased health research funding, especially in poorer countries, will reduce the burden of lupus at the population level. Beyond all this, now more than ever, families and health systems around the world must work together not only to overcome COVID-19, but to assure the availability of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to patients in the developing world.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak here.