Dozens of antibody tests for the novel coronavirus have become available in recent weeks. And early results from studies of such serological assays in the U.S. and around the world have swept headlines. Despite optimism about these tests possibly becoming the key to a return to normal life, experts say the reality is complicated and depends on how results are used.

Antibody tests could help scientists understand the extent of COVID-19’s spread in populations. Because of limitations in testing accuracy and a plethora of unknowns about immunity itself, however, they are less informative about an individual’s past exposure or protection against future infection.

“The focus right now is primarily epidemiological,” says Tara Smith, a professor of epidemiology at the Kent State University College of Public Health. That approach means trying to figure out the percentage of the population that has already been infected even if some individuals never showed symptoms. “This will allow us to better calculate the fatality rate and to determine how far we still have to go to reach [infection] levels that would place us in the range of herd immunity,” or when a large proportion of a population has become immune to a disease because of vaccination or past infection, she says. “It will also allow us to start looking at duration of immunity.”

Serological surveys have already been conducted in communities across the U.S., and their findings vary widely. Estimates of positive antibody prevalence range from almost 25 percent in New York City and 32 percent in Chelsea, Mass., to between 2.8 and 5.6 percent in Los Angeles County and 2.8 percent in Santa Clara County in California.

These results support what experts already suspected based on case studies of asymptomatic transmission: COVID-19 is much more widespread than hospital data would suggest. But several of the studies have been criticized by scientists, who have raised red flags about sampling methods, potentially flawed statistics and results that are first announced as press releases rather than as peer-reviewed or even preprint studies.

These methodological problems and perceived lack of transparency are exacerbated by the ubiquity of subpar assays. Many of the tests currently flooding the market have not been verified by third parties. And even those that have received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration might not be accurate enough to assess disease prevalence levels outside of hotspots.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security maintains and regularly updates a Web site that lists key characteristics of many of the serological tests for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, on the market and in development. Experts recommend that tests be validated in studies that include at least 100 positive and negative patients whose infection status is confirmed against a reference standard such as diagnostic test results and symptoms. Antibody tests currently on the market have been validated in samples ranging from only a few dozen individuals to more than 1,000. As of this writing, that source lists that tests approved for research or individual use in the U.S. accurately detect antibodies in people who have them—a statistic known as sensitivity—between 82 and 100 percent of the time. Their ability to correctly identify antibodies only in those who actually have them—known as specificity—ranges from 91 to 100 percent.

On the surface, those numbers seem pretty good. But “threshold is set by context,” says Sarah Cobey, an associate professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Chicago. “So if the seroprevalence,” or the proportion of the community that has antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, “is 3 percent versus 5 percent, you have to have an exceedingly good test” to distinguish that, she says. “If you’re [only] trying to identify if the prevalence is above 50 percent or below 50 percent, you can get away with a test that’s maybe less good. But nobody is in that category [with COVID-19].”

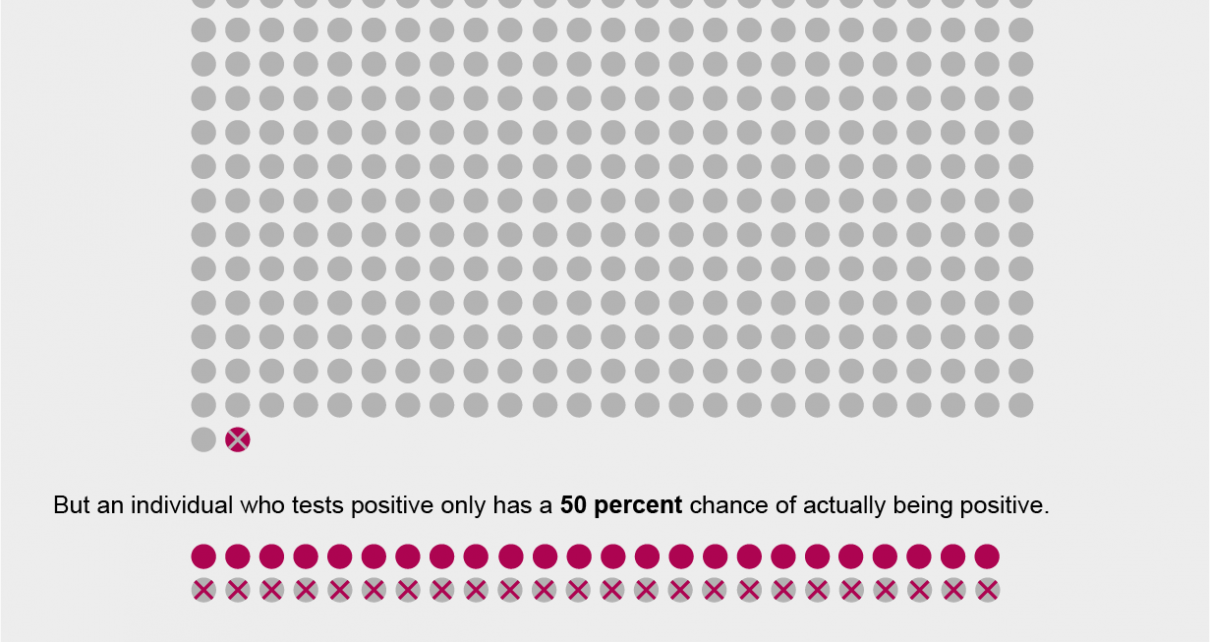

This variability in what constitutes an acceptable test arises from the fact that in populations with a higher prevalence of a disease or past exposure to it, true positives (individuals who test positive and have antibodies to the illness from a prior infection) and false negatives (those who test negative but actually have antibodies) are more common. Meanwhile in populations with a lower prevalence, tests are more likely to give false positives.

The preprint study on an antibody test in Santa Clara County claimed that it had a specificity of 99.5 percent. But University of Washington epidemiologist Trevor Bedford argued in a Twitter thread that if that test instead had a 98.5 percent specificity—well within the possible range of uncertainty defined by the researchers—all of the study’s “positive results” could have been false positives.

Some of these concerns can be managed by building models that account for uncertainty. But overestimates of COVID-19’s spread could lead to underestimates of fatality and hospitalization rates—or excessive confidence about herd immunity. Such immunity is currently thought to require about 70 percent of the population to have been exposed—a rate even hotspots such as New York are likely nowhere near. Any of these errors could, in turn, lead to policies that are bad for public health.

Furthermore, overestimating the prevalence of people with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies could create an unwarranted sense of security about the diagnostic role tests can play. Because false positives are more common in places with low disease prevalence, Smith notes, “there is the potential for individuals to be misled regarding their [antibody] status. If they are false positive, they may believe they are immune when they are not and may relax protective measures.”

At this stage, experts warn that even the best SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests have little use at the individual level. More than four months after doctors in Wuhan, China, first identified the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, scientists are still scrambling to understand how our immune system responds to it. Although research increasingly shows that most people who have been infected probably produce antibodies to the virus, it is not yet clear whether those antibodies prevent reinfection or how long any immunity will last.

“We don’t know the natural [course] of the disease. All we can do is [say] that if you have a good [antibody] test, and you trust the result, and you’re positive, you did have exposure,” says May Chu, a clinical professor of epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health. “We do not know if [those antibodies are] protective. And we won’t know for months to come—until somebody else who’s been infected before gets exposed to the virus again, and we see whether they get sick or not,” says Chu, who is also a member of a World Health Organization expert group focused on infection control and prevention for the COVID-19 epidemic. In fact, on April 24 the WHO released a scientific brief explicitly cautioning against the use of so-called “immunity passports” or “risk-free certificates.” There have been a few reports of individuals testing positive for the virus after recovering and testing negative. But they have not been shown to have been reinfected. Some experts think antibody tests might be able to help determine whether such cases are the result of reinfection or “redetection” cased by a clinical relapse.

While scientists work to get a handle on how the pandemic is playing out in different populations around the world, testing for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 remains largely in the research domain. Nationwide surveys that are now underway aim to collect samples from tens of thousands of people throughout the U.S. over the next two years.

Testing capacity for active infections remains uneven around the country. And antibody tests offer an opportunity to shine a light on the situation in places that have not had the resources to confirm active cases. “It is going to be extremely important for different regions to do their own [serological] surveys to identify exactly how much transmission has occurred,” Cobey says. “This is how you adapt interventions for the local situation.”

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak here.