Colleges and universities in the U.S. are currently being forced to make a seemingly impossible decision between in-person and remote classes this fall. As a professor, I am all too familiar with both the pros and cons of bringing college students back to campus. Students benefit from the full college experience filled with dorm living, engaging learning opportunities and social interactions. However, bringing students back to campus requires Herculean efforts by institutions to assure everyone’s safety. And even with all of this planning, many faculty are more vulnerable to the virus given their advanced age and associated preexisting conditions.

Moreover, the educational system’s “Sophie’s Choice” situation is not limited to college students; it also exists for students from pre-K to high school. How will they socially distance when most classrooms are already overcrowded? Will younger children be able to adapt to wearing masks for eight hours each day and refrain from touching their faces?

From my behavioral neuroscience perspective, the solution to this dilemma is clear. As we have heard time and time before, strategic behaviors such as wearing masks, handwashing, and physical distancing will buy us time while scientists work on vaccines and effective therapeutic options. A hopeful study posted in April describing informed agent–based models generated by computer scientist De Kai (University of California, Berkeley, and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) and colleagues indicated a drastic decrease in COVID-19 infection rates if 80 percent of the population wore masks. In July, additional computer-generated models published by a research team in the Netherlands led by epidemiologist Alexandra Teslya indicated that increased awareness about self-imposed behavioral modifications, including distancing, mask-wearing and handwashing, can greatly reduce COVID-19 prevalence.

Despite these encouraging reports, strategic media campaigns to facilitate these changes have yet to emerge in this health crisis. In addition to the critical laboratory research needed to develop an effective vaccine and treatments, it’s time to focus on evidence-based behavioral initiatives to create a safer world for our students to return to campuses and classes as soon as possible. After all, the host behavior is as critical as cellular immune responses in the body’s defense against disease. Many animals avoid pathogens through behaviors such as licking their wounds and social grooming.

Humans also benefit from strategic behavioral responses to reduce the pervasiveness of pathogens. With the most impressive neural profile of any species on earth, we should be able to develop an effective fight against a virus. After all, only humans can derive computational modeling and effective therapeutics and vaccines. A quick perusal of our history with behavioral interventions reminds us that behavioral modification initiatives should be viewed as no less essential than laboratory investigations in health crises.

In the mid-19th century, more women were dying from a condition referred to as “childbed fever” at the Vienna General Hospital in Austria if their babies were delivered by medical doctors rather than midwives. A systematic investigation by the physician Ignaz Semmelweis determined that the fever resulted from the doctors conducting autopsies during the mornings, then delivering babies in the afternoon without washing their hands. Once handwashing protocols were implemented in the Austrian hospital, the rates of women dying from childbed fever plummeted. Even with the dramatic decreases in death, however, doctors were very slow to adopt this early evidence of pathogen transmission and resisted the hygiene recommendations.

Despite its rocky start, the importance of behavioral changes in health promotion has been noted in the emergence of effective information campaigns throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries. Mass media campaigns have successfully decreased risky behaviors such as alcohol/tobacco use, failure to use seatbelts, and reluctance to have cancer screenings. One of the most successful media campaigns to modify behavior in the U.S. goes back to 1944 and a humanized forest animal called Smokey Bear (and later also known as Smokey the Bear).

Created to decrease risky behaviors associated with the dangerous spread of forest fires, the jean- and hat-wearing bear was pictured in early campaign posters declaring that each individual could make a difference by following safety guidelines. His tagline, familiar to generations of kids who saw it on posters and heard Smokey say it on TV: “Only you can prevent forest fires.” Three quarters of a century later, a comprehensive Web site with educational materials is maintained by the Ad Council, The National Association of Foresters, and the U.S. Forest Service (see SmokeyBear.com). This campaign is an excellent example of an effective behavioral modification campaign.

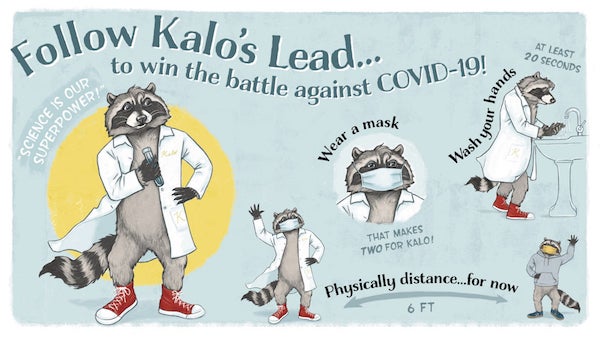

While we wait for an effective vaccine for COVID-19, we need a Smokey Bear moment to turn the tide and change the outcome probabilities for various educational scenarios this fall. A new and intentional hero as appealing as Smokey Bear may be just what the doctor ordered to shift the unacceptable contingency forecasts in the coronavirus health storm. In collaboration with illustrator Katie McBride, I have created an intentional hero—a raccoon named Kalo (after the Greek term for health or to make whole)—as an evidence-based fictional hero to lead the way on healthy behaviors to diminish the spread of the virus until a vaccine is available.

This proposed hero declares its superpower to be science and recommends behaviors that raccoons are already doing in nature: washing their hands (well, they’re actually foraging for food in nature, but that can be our secret); mask-wearing and social distancing. The Kalo character targets children who, one hopes, recruit their parents and other family members to follow along with the proposed recommendations. Incentives for the targeted behaviors can range from a sense of personal accomplishment after documenting healthy behaviors each week to other rewards that may emerge to reinforce children’s’ commitment to the behaviors (stickers or other treats from parents, schools or participating businesses).

If a majority of the population accepts the Kalo Challenge for the rest of the summer, our prospects for resuming the educational and social experiences we are all craving become more realistic. After our initial botched response to the virus, I have confidence that our children can help push us through this pandemic. My daughters were often little spies who loved to monitor their parents’ behavior, frequently admonishing their mom and dad for breaking a rule.

Last fall my lab published a study that described how we trained rats raised in enriched environments to drive little cars for Froot Loop treats. If we can teach rats to drive cars for sweet cereal rewards, surely humans can be trained to adopt these simple behaviors for the rewards of survival and the return to our pre-COVID social lives. Our children deserve the opportunity to return to their classes, neighborhood barbeques, recitals, church services, sporting events, birthday parties — everything their parents enjoyed during their formative years. As an example of a behavioral modification media campaign, a poster draft for Kalo is compared to the initial poster for the Smokey Bear campaign. In the absence of a current national program for surviving the COVID-19 pandemic, I encourage us to follow Kalo’s lead and the superpower of science through these turbulent times to win the battle against COVID-19.