Puerto Rico just can’t catch a break. Since December 28th of 2019, the southwestern coast of the island has experienced nearly four thousand earthquakes of M2.5 or greater. Since being severely shaken and damaged in January by a stout M6.4, plus a handful of M5+ temblors, the seismic sequence had settled into a pattern of moderate magnitude quakes, rarely exceeding M4.0 And with the onset of the novel coronavirus, most of the island’s shaken citizens had returned to their homes, hoping the worst was over.

Tectonic faults, unfortunately, are heedless of human needs. Early on the morning of May 2nd, a hefty M5.4 hit, sending folks fleeing from freshly damaged homes. The sequence isn’t finished, and there’s no guarantee a larger earthquake won’t happen in the near future.

This is the unfortunate reality of Puerto Rico’s tectonic milieu. The island was born in fire, and is now squeezed between two massive plates. Today, we’ll take a look at the island’s general tectonic setting and seismic risk. Next time, we’ll zoom in on the fault zone responsible for the current excitement. And then in the hopefully not-too-distant future, we’ll have a look at some really neat tectonic features that are marvelously demonstrated in the Caribbean.

A Tectonic Overview

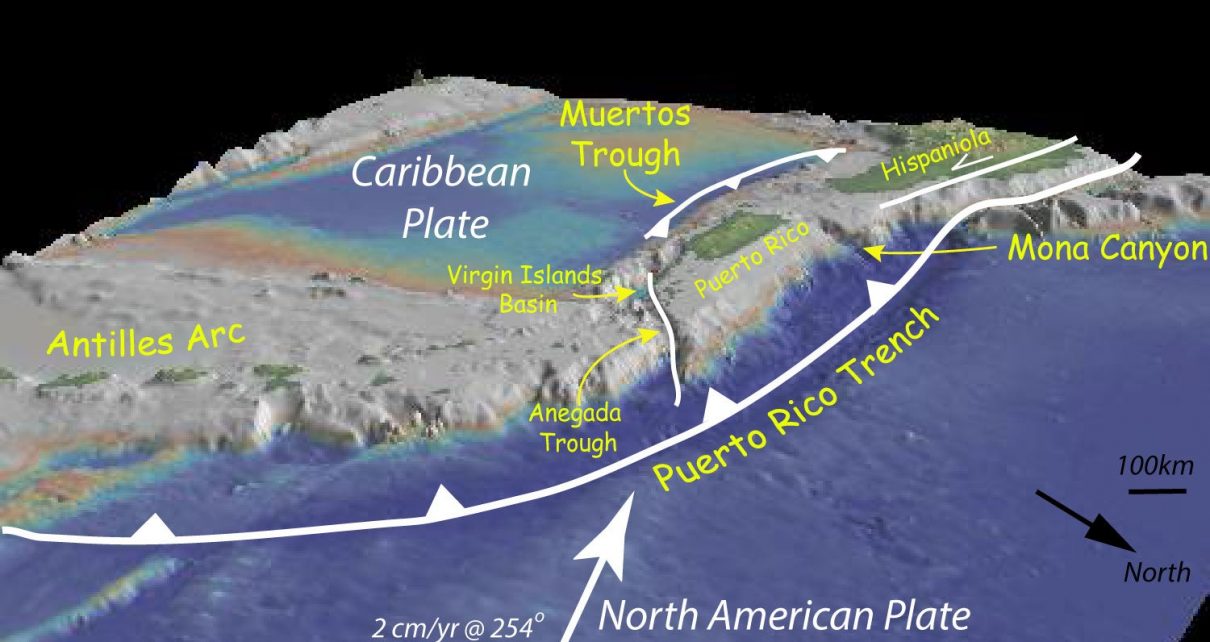

Puerto Rico is a small island surrounded by complex fault systems. It’s stuck between the Caribbean and North American plates as they converge in some places and slide past each other in others. The Caribbean plate is moving east relative to the North American plate at a rate of around 2 centimeters a year, which is a fair amount of motion to have to accomodate. This is accomplished by a complicated regime of transform faulting, collision, and subduction that we’re only beginning to untangle. Here’s a general outline of the situation as far as we currently understand it:

To the north of the island, a portion of the North American plate subducts obliquely beneath the Caribbean plate along the 1,090 kilometer-long Puerto Rico Trench. You’ll find the deepest part of the Atlantic here, a respectable 8,380 meters. To give some perspective on that depth: if you popped K2 or Everest in there, you’d be able to reach from sea level to summit in an easy day hike.

Because of the oblique convergence of the two plates, there are also a number of gnarly transform faults. One of the fault systems, though submarine, closely resembles the San Andreas in California. It was named for Betty Bunce, a very awesome oceanographer we’ll be meeting in the near future.

Despite the depth of the trench, subduction here isn’t causing active volcanism. Eruptions are one hazard Puerto Rico doesn’t need to worry about. That concern is reserved for the volcanic arc of the Lesser Antilles to the east, where the North American plate is roughly perpendicular to the Caribbean plate and subducting beneath it.

West of Puerto Rico, the 30 kilometer-wide submarine Mona Canyon is a result of east-west rifting. This fault system probably generated one of Puerto Rico’s largest known earthquakes, the M7.5 1918 San Fermin earthquake. (Yep, that happened during the Spanish Flu pandemic. Puerto Rico is indeed two for two on the earthquakes-during-modern- pandemics front.)

And now we arrive at the southern boundary of the island, where the current seismic excitement is happening. Offshore, we encounter the Muertos Trough and its associated fold-and-thrust belt. Here, slices of crust are shoved beneath other slices. This has in the past been interpreted as another subduction zone, but there’s room for doubt.

All of that faulting continues onto land throughout the island. Active faults show a wild variety of stresses for such a small landmass: northeast-southwest compression, northwest-southeast extension, and west-northwest to east-southeast-trending left-lateral faulting all make their fateful mark.

Puerto Rico’s Shaky Past, Present, and Future

It’s probably no surprise by now that Puerto Rico has experienced at least one or two major earthquakes per century for at least the last 500 years. Smaller but still substantial quakes happen every year. This is not the place to be if you don’t want to feel the ground shake!

A lot of people are in harm’s way. Puerto Rico’s population density is 441 people per square kilometer, the highest in the United States. Southwestern Puerto Rico is undergoing rapid development, with homes, businesses, and infrastructure being constructed on soft alluvial and marine sediments, which are spectacularly vulnerable to liquefaction.

Despite all that, Puerto Rico’s seismic hazards are woefully neglected. Many currently active faults have been unrecognized until they rupture. Improvements in the Puerto Rico Seismic Network’s equipment and operations haven’t yet been able to keep pace with need. Geological studies have only begun to find the previously-unrecognized faults that threaten future mayhem.

The current swarm is happening along a fault system that was only just starting to be recognized and mapped. We’ll explore that system in our next installment.

References:

Giunta, G. and Orioli, S. (2011): The Caribbean Plate Evolution: Trying to Resolve a Very Complicated Tectonic Puzzle. New Frontiers in Tectonic Research – General Problems, Sedimentary Basins and Island Arcs

Granja Bruña et al (2009): Morphotectonics of the central Muertos thrust belt and Muertos Trough. Marine Geology 263

Granja Bruña et al (2015): Shallower structure and geomorphology of the southern Puerto Rico offshore margin. Marine and Petroleum Geology 67

Monroe, W.H. (1980): Geology of the Middle Tertiary formations of Puerto Rico. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 953

NOAA Ocean Explorer: Puerto Rico Trench 2003. Last accessed 5/6/2020

NOAA Ocean Explorer: The Puerto Rico Trench: Implications for Plate Tectonics and Earthquake and Tsunami Hazards. Last accessed 5/6/2020

Ortega-Ariza, Diana (2016): Sequence Stratigraphy and Depositional Controls on Oligocene-Miocene Caribbean Carbonate-Dominated Systems, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. PhD Thesis, University of Kansas.

Roig-Silva, C. (2010): Geology and structure of the North Boquerón Bay–Punta Montalva fault system. M.Sc. Thesis, Department of Geology, University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez.

Roig-Silva et al (2013): The northwest trending North Boquerón Bay-Punta Montalva fault zone: A through going active fault system in southwestern Puerto Rico. Seismological Research Letters 84