1970

A Lunar “Tablespoonful”

“In the broad, flat lunar maria, or ‘seas’ (such as Mare Tranquillitatis, the site of the Apollo 11 manned landing), the depths of craters that have reached bedrock indicate a regolith thickness of from five to 10 meters. Thus the Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., did not come within several meters of solid rock at Tranquillity Base, and the geology picks they had brought along for the purpose of chipping specimens off outcrops were superfluous. They stood and walked on top of the regolith, and the lunar sample they returned was collected, with scoop and tongs, from this layer of rock debris. Our own group at the Smithsonian Institution Astrophysical Observatory has been working with 16 grams (about a tablespoonful) of the soil. —John A. Wood”

1920

The Mango Bears Fruit

“The U.S. Department of Agriculture has secured through its agricultural explorers and by exchange with the British East Indian departments of agriculture one of the largest collection of mango varieties in the world, and now has in fruit, at its plant introduction station at Miami, Fla., about 20 varieties. It is said that these selected varieties strikingly belie the many unkind things that have been said about the mango. Some of them have hardly more fiber in them than a freestone peach, and can be cut open lengthwise and eaten as easily with a spoon as a cantaloupe.”

Schools and the Army

“The National Research Council announces that the mental tests which were used with striking success in the Army during the war are to be used on a large scale in American public schools. A program of group tests has been worked out which will make it possible to conduct wholesale surveys of schools annually, or even semiannually, so that grade classification and individual educational treatment can be adjusted with desirable frequency.”

1870

Of Toadstools and Whales

“It is a simple matter of fact and of every day observation that all forms of animal work are the result of the reception and assimilation of a few cubic feet of oxygen, a few ounces of water, of starch, of fat, and of flesh. In a chemical point of view man may be defined to be something of this sort. That great authority, Professor [Thomas] Huxley, has lately been discussing what he calls ‘protoplasm, or ‘the physical basis of life.’ He seeks for that community of faculty which exists between the mossy, rock-incrusted lichen, and the painter or botanist that studies it. Professor Huxley has not proved, and it is impossible for him to prove, that these protoplasms may not have essential points of difference. Physiologists cannot yet tell us how it is that ‘of four cells absolutely identical in organic structure and composition, one will grow into Socrates, another into a toadstool, one into a cockchafer, another into a whale.’”

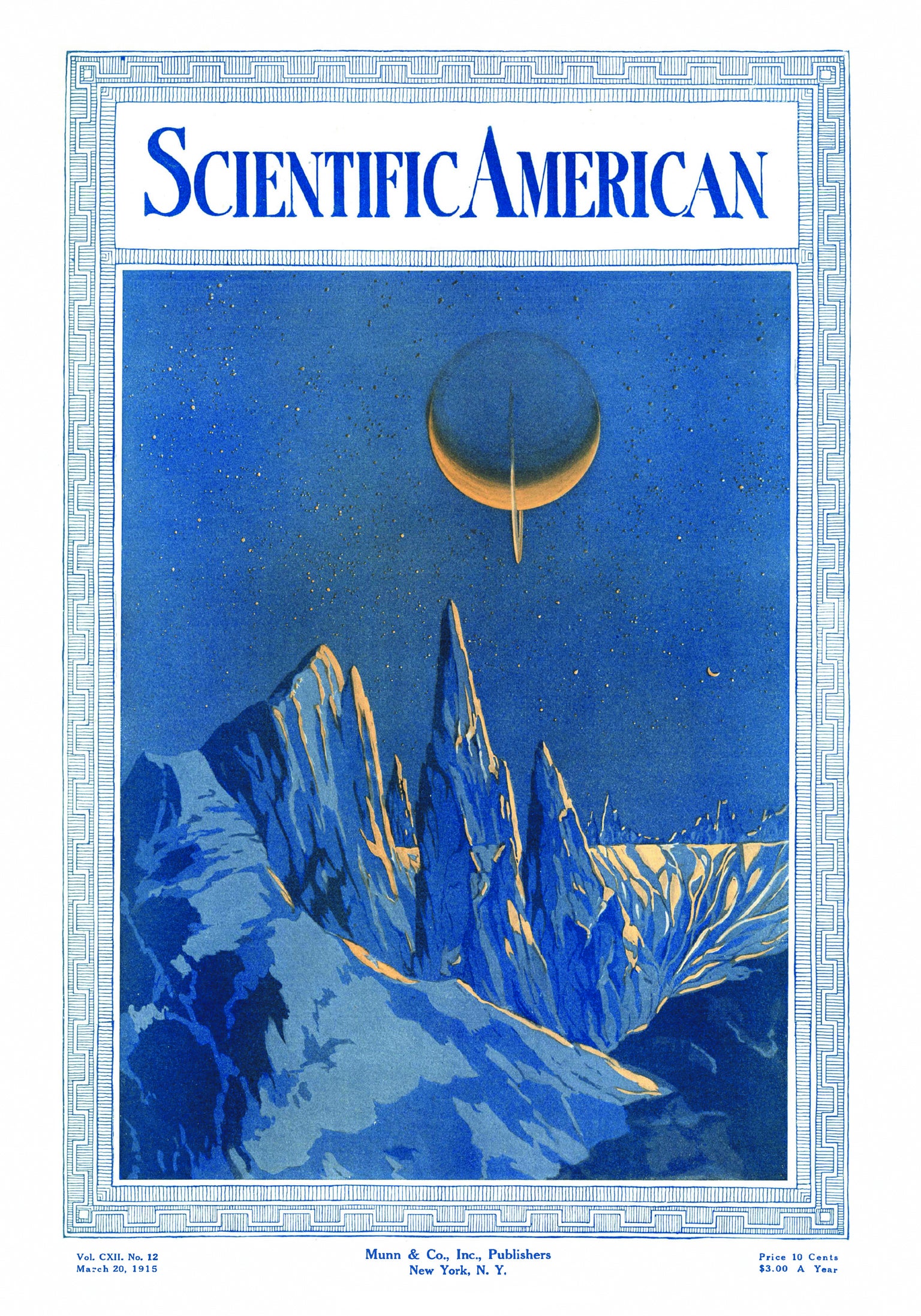

EPIC TALES

Space Exploration

Planets and stars are as much a product of “nature’s laboratory” as Homo sapiens. And while our species examines the information gleaned from the universe that surrounds us, we also have an emotional sense of wonder at revealing the secrets of nature and our place within it. (This magazine may tend to leave emotion to neuroscience, as our focus is on scientific data—but we also publish poetry.) From the invention of the first telescope in 1608 to the discovery of the Milky Way galaxy’s place in Laniakea—a great river of galaxies streaming toward a giant hidden gravity source—our exploration of the universe so far follows a trend: we explore with instruments and with our imaginations. And one day we will go ourselves, leaving our footprints across the universe. —D.S.