As COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations remain high across the country, our weakened public health system has never been more frustrating to front line clinicians. While it’s tempting to blame politicians, it’s also insufficient. To understand why this pandemic has had such deleterious effects, we must examine why the study of diagnosis and treatment of disease separated itself from the study of preventing disease—or, more succinctly, why medicine and public health are considered apart from each other.

Tracing this unfortunate disconnect leads us to a cause from 110 years ago: the 1910 Flexner report.

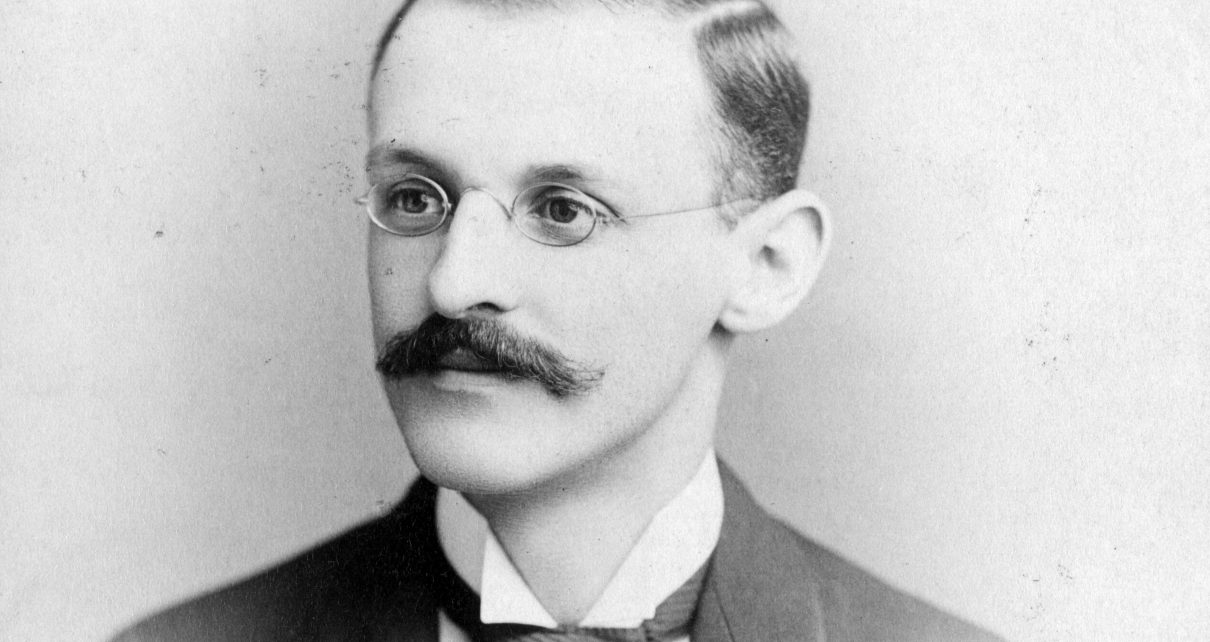

In the early 1900s, the length, focus and quality of medical training differed from school to school, resulting in significant variability from doctor to doctor. Spurred by this disarray, the American Medical Association commissioned the Carnegie Foundation to help reform medical education. Together they hired Abraham Flexner, founder of a successful prep school and the future founding director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, to assess the state of medical education. After visiting every medical school in North America, he produced the report.

The Flexner report—and the money tied to its implementation—is the medical education system we’re familiar with today: competitive admission criteria, traditional pedagogy and the scientific method as its central tenets. The report established the individual biomedical model, which focuses exclusively on biologic causes of disease, excluding any social and environmental factors, as the gold standard.

It also led to the disproportionate closing of historically Black medical colleges, contributing to physician workforce disparities that still exist today, and effectively cleaved the study of medicine from the study of public health.

Even over a century later, some modern medical academics cling to this paradigm. Former University of Pennsylvania medical school dean Stanley Goldfarb propelled this idea to prime time with a 2019 Wall Street Journal op-ed titled “Take Two Aspirin and Call Me by My Pronouns,” in which he refers to topics such as firearms violence, racial bias, health disparities and climate change as “progressive causes only tangentially related to treating illness” and not worthy of inclusion in the curriculum.

Goldfarb hasn’t been the only one to echo the Flexner report. Thomas Huddle, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, dismissed advocacy for societal good as out of scope in academia in a 2011 article in Academic Medicine, stating: “Although advocacy may coexist alongside the core university activities of research and education, insofar as it infects those activities, advocacy is likely to subvert them, as advocacy seeks change rather than knowledge.”

But Goldfarb and Huddle and the people who agree with them are a minority in the medical community.

The American College of Physicians strongly rebutted Goldfarb’s essay and directed detractors to its public health policy statements. In its recent position statement, the Society for General Internal Medicine calls for cross-cutting action to address the social determinants of health, declaring that “direct policy action will have the most far-reaching impact on improving health, equity, and well-being.” The American Academy of Family Physicians lays out sweeping policy recommendations to promote health equity, and the American Academy of Pediatrics calls for comprehensive work to combat racism as “health equity is unachievable unless racism is addressed.”

Even the American Medical Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics require physicians to actively “support access to medical care for all people.” The Physician’s Charter recognizes the “primacy of patient welfare, patient autonomy and social justice.”

Despite these bold calls to action and majority support, the Flexner report still has a grasp on medical education. To be fair, no one cites the Flexner report in defending the medical status quo, and the biopsychosocial model has supplanted the biomedical model in many settings.

But the Flexner report’s legacy wears on in this “tradition of excellence” that minimizes social and environmental factors and in doing so, undermines our understanding and treatment of disease.

For example, researchers often cite the individual attribute of race as a risk factor for disease without interrogating the associated environmental experience of racism. Similarly, the lens in medical education is often inclusive of poverty but not oppression, race but not racism, sex but not sexism, and homosexuality but not homophobia. We can see the biomedical model’s influence in the field of psychiatry in the stark division of labor between the physician who assesses the patient’s neurobiology and treats with prescription drugs, and the therapist who assesses psychosocial factors and treats with therapy.

As long as the scientific method exclusively continues to dictate what physicians do, medicine will resist the responsibility to engage in upstream work to dismantle social causes of disease. Advocacy—defined by physician advocates as activities “promoting the role of science and evidenced-based medicine in the creation of health and social policy”—has been treated as if it’s unscientific and therefore an unworthy endeavor, even though, through their various professional organizations’ public policy positions, most physicians think it’s just the opposite. While advocacy is taught in some training programs, it is not universal and the curriculum is heterogeneous. Lack of mentorship, sponsorship and funding for advocacy in academic medicine pose significant challenges to incorporation of it into the physician career.

We’re seeing similar conditions that led up to the commission of the Flexner report years ago. The purpose of the report was to standardize education so that doctors would be uniformly trained. Advocacy education, while popular, isn’t standardized, at least not in the right way; most support it, but only some get it.

But the U.S. is now at a critical public health turning point, and advocacy in medicine can no longer be optional. The dual crises of COVID-19 and police brutality have captured our collective attention and exposed our considerable vulnerabilities. Current COVID-19 statistics show infection and mortality rates in the U.S. to be among the highest in the world; our daily infection rate recently hit 70,000. Police brutality is a uniquely American problem; over 1,000 people are killed by the police each year, while in other G7 nations such incidents are exceedingly rare. Black and brown communities are disproportionately affected by both COVID-19 and police brutality, crystallizing racism as a fundamental public health problem in America.

The cracks in our nation’s health exposed by COVID-19 demonstrate that we still need to evolve from these clearly outdated assumptions of yesteryear. Medicine as a discipline needs a strong public health foundation. The most effective public health strategies to combat COVID-19— universal masking, test/trace/isolate, and closures—have all been thwarted in the name of politics.

To begin to reintegrate medicine and public health, we must incorporate advocacy as a core competency across the educational spectrum: from medical school to residency to continuing medical education. Public health is not just for politicians. We must equip physicians with the necessary skills to effectively advocate for the policies we so desperately need to care for our patients.

The Flexner report needs to be supplanted by another document that stitches medicine and public health back together. A replacement for the Flexner report can catalyze concrete action and may provide cover and justification for those people who’ve met resistance while trying to incorporate advocacy into medical education and practice.

Even if it is only a symbolic gesture to indicate abandonment of outdated ways of thinking, the American Medical Association would be wise to commission another report to show that Flexner’s thinking, while revolutionary for his time, isn’t applicable anymore.