A persistent falsehood has been circulating on social media: the number of COVID deaths is much lower than the official statistic of more than 218,000, and therefore the danger of the disease has been overblown. In August President Trump retweeted a post claiming that only 6 percent of these reported deaths were actually from COVID-19. (The tweet originated from a follower of the debunked conspiracy fantasy QAnon.) Twitter removed the post for containing false information, but fabrications such as these continue to spread. U.S. Representative Roger Marshall of Kansas complained in September that Facebook had removed a post in which he claimed that 94 percent of COVID-19 deaths reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “were the result of 2-3 additional serious illnesses and were of advanced age.”

Now some facts: Researchers know beyond a doubt that the number of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. have surpassed 200,000. These numbers are supported by three lines of evidence, including death certificates. The inaccurate idea that only 6 percent of the deaths were really caused by the coronavirus is “a gross misinterpretation” of how death certificates work, says Robert Anderson, lead mortality statistician at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics.

The scope of the coronavirus’s deadly toll is clear, even if final numbers will not be known until the pandemic is over. “We’re pretty confident about the scale and order of magnitude of deaths, but we’re not clear on the exact number yet,” says Justin Lessler, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. To understand why the figures contain some uncertainty, it is important to know how they are collected and calculated.

The first source of death data is called case surveillance. Health care providers are required to report cases and deaths from certain diseases, including measles, mumps and now COVID-19, to their state’s health department, which, in turn, passes this information along to the CDC, Anderson says. The surveillance data are a kind of “quick and dirty” accounting, says Shawna Webster, executive director of the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. The states gather all the information they can on these diseases, but this is the first pass of the accounting—no one has time to double-check the information or look for missing lab tests, she says. For that, you have to look for the next source of information: vital records.

This second line of evidence comes from the National Vital Statistics System, which records birth and death certificates. Every time somebody dies, a death certificate is filed in the state where the death occurred. And after the records are registered at a state level, they are sent to the National Center for Health Statistics, which tracks deaths at a national level. Death certificates are not filed in the system until outstanding test results are in and the information is as complete as possible. By the time a record gets to the vital records system, “it is as close to perfect as it’s going to get,” Webster says.

A physician, medical examiner or coroner fills out the cause of mortality on the death certificate, and they are instructed to include only those conditions that caused or contributed to death, Anderson says. One field lists the sequence of events leading to the death. “What we’re really trying to get at is the condition or disease that started the chain of events leading to the death,” Anderson says. “For COVID-19, that might be something like acute respiratory distress due to pneumonia due to COVID-19.” A second part of the certificate lists other significant conditions that may have contributed to the death yet were not part of the sequence of events that led up to it, he says. These are called comorbidities, and while they can be contributing factors, they cannot be directly involved in the chain of cause and effect that ended in death. Preexisting medical conditions such as diabetes or heart disease are common comorbidities, and they can make a person more vulnerable to the coronavirus, Anderson says, “but the fact is: they’re not dying from that preexisting condition.”

“When we ask if COVID killed somebody, it means ‘Did they die sooner than they would have if they didn’t have the virus?’” Lessler says. Even such a person with a potentially life-shortening preexisting condition such as heart disease or diabetes may have lived another five, 10 or more years, had they not become infected with COVID-19.

The 6 percent number touted by Trump and QAnon comes from a weekly CDC report stating that in 6 percent of the coronavirus mortality cases it counted, COVID-19 was the only condition listed on the death certificate. That observation likely means that those death certificates were incomplete because the certifiers only gave the underlying cause of death and not the full causal sequence that led to it, Anderson says. Even someone who does not have a preexisting condition and dies from COVID-19 will also have comorbidities in the form of symptoms, such as respiratory failure, caused by the coronavirus. The idea that a death certificate with ailments listed in addition to COVID-19 means that the person did not really die from the virus is simply false, Anderson says.

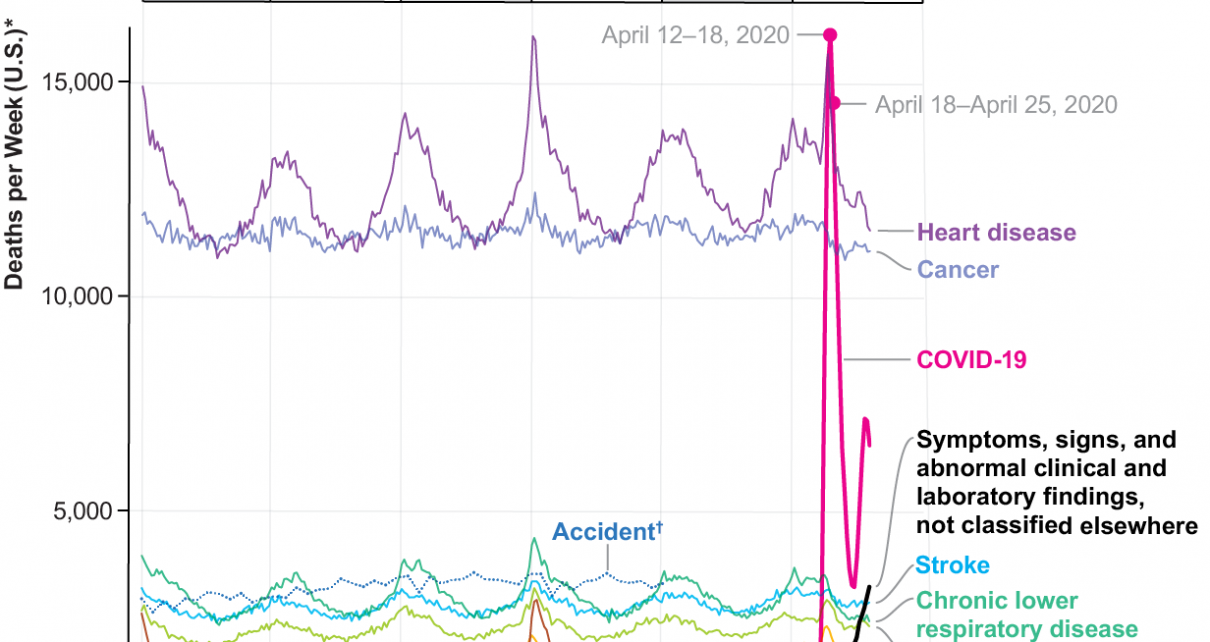

The surveillance and vital statistics data provide a pretty good picture of how many deaths are attributable to the coronavirus, but they do not capture all of them, and that is where the final line of evidence come in: excess deaths. They are the number of deaths that occur above and beyond the historical pattern for that time period, says Steven Woolf, a physician and population health researcher at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine. In a paper published in JAMA this month, Woolf and his colleagues examined death records in the U.S. from March 1 through August 1 and compared them with the expected mortality numbers. They found that there was a 20 percent increase in deaths during this time period—for a total of 225,530 excess deaths—compared with previous years.

Two thirds of these cases were attributed to COVID-19 on the death certificates, and Woolf says there are two types of explanations for the rest: Some of them were COVID-19 deaths that simply were not documented as such, perhaps because the person died at home and was never tested or because the certificate was miscoded. And some of the extra deaths were probably a consequence of the pandemic yet not necessarily the virus itself. For instance, he says, imagine a patient with chest pain who is scared to go to the hospital because they do not want to get the virus and then dies of a heart attack. Woolf calls this “indirect mortality.” “The deaths aren’t literally caused by the virus itself but the pandemic is claiming lives,” he says.

The numbers in Woolf’s study come from provisional death data, the kind that the CDC has not yet checked for miscoding or other issues, so it comes with some degree of imprecision. What builds his confidence in these results, however, is the fact that they have been replicated numerous times by his group and others. “All serious analyses of these data are showing that the number of deaths we’re hearing on the news is an undercount,” he says.

COVID-19 is now the third leading cause of death in the U.S. Whether the number of lives cut short add up to 218,511, 219,681 or 219,541—as reported by the CDC, Johns Hopkins University and the New York Times, respectively, on October 19—it’s a staggering number of lives cut short.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.