We all know the story: 66 million years ago, a giant asteroid crashed into Earth, killing off three-quarters of all species, including most of the dinosaurs. Researchers suspect that the impact caused the extinction by kicking up a cloud of dust and tiny droplets called aerosols that plunged the planet into something like a nuclear winter.

“These components in the atmosphere drove global cooling and darkness that would have stopped photosynthesis from occurring, ultimately shutting down the food chain.”

Shelby Lyons, a recent PhD graduate from Penn State University.

But scientists have also found lots of soot in the geologic layers deposited immediately after the asteroid impact. And the soot may have been part of the killing mechanism too—depending on where it came from.

Some of the soot probably came from wildfires that erupted around the planet following the impact. But most of these particles would have lingered in the lower atmosphere for only a few weeks, and wouldn’t have had much of an effect on global climate.

But scientists hypothesize that soot may also have come from the very rocks that the asteroid pulverized when it struck. If those rocks contained significant amounts of organic matter—such as the remains of marine organisms—it would have burned up on impact, sending soot shooting up into the stratosphere. In that case, soot would have spread around the globe in a matter of hours and stayed there for years. And it would have radically altered Earth’s climate.

So Lyons and her team set out to identify the source of the soot. They looked at chemicals known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, which are another byproduct of combustion.

“You can find PAHs in meat or veggies that you grill. You can find them from the exhaust of a car. You can also find them in smoke and debris from the wildfires today out west.”

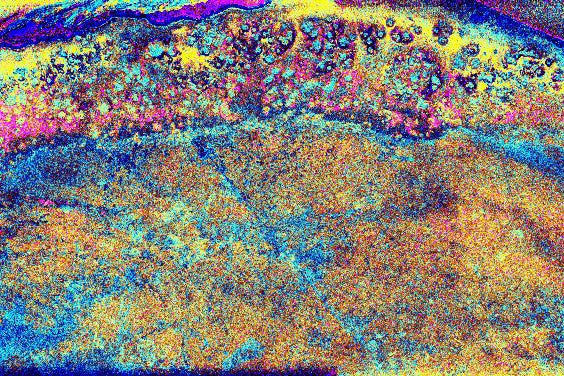

PAHs are made up of fused rings of carbon atoms—think of chicken wire. To determine the origin of the soot, the researchers looked at the structure and chemistry of the PAHs buried along with it. Specifically, the researchers looked for groups of atoms that stick off the rings like spikes. PAHs generated from burning wood don’t have many spikes, but PAHs from burning fossil carbon—like what would have been in the target rocks—have more.

Lyons and her team found that most of the PAHs deposited after the impact were spiky, which suggests that soot from the rocks hit by the asteroid played a major role in the mass extinction.

“There was more dust and more sulfate aerosols than soot, but soot is a stronger blocker of sunlight than either of those two. So a small amount of soot can drive large reductions in sunlight.”

The findings are in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Shelby L. Lyons et al, Organic matter from the Chicxulub crater exacerbated the K–Pg impact winter]

The results suggest that the devastation of this very sooty asteroid impact may be due in part to a fluke of geography: the space rock smashed into the Gulf of Mexico, where the sediments were rich in organic matter. They still are—the region produces large amounts of oil today.

“Where it had occurred was likely one of the reasons that it led to a major mass extinction. It was kind of the perfect storm, or the perfect asteroid impact, I guess you could call it.”

—Julia Rosen

(The above text is a transcript of this podcast)