In 1947, the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl set sail from Peru, on a balsa wood raft called Kon-Tiki. As he explained a few years later in the documentary of the same name, Heyerdahl was convinced that indigenous people from South America had used a similar craft to settle Polynesia.

<<Kon-Tiki clip: “The only way to test my theory was to build one of these rafts, on the basis of the Spanish descriptions, launch it into the sea off the coast of Peru and find out if wind and current would in fact waft us ashore on South Pacific islands.”>>

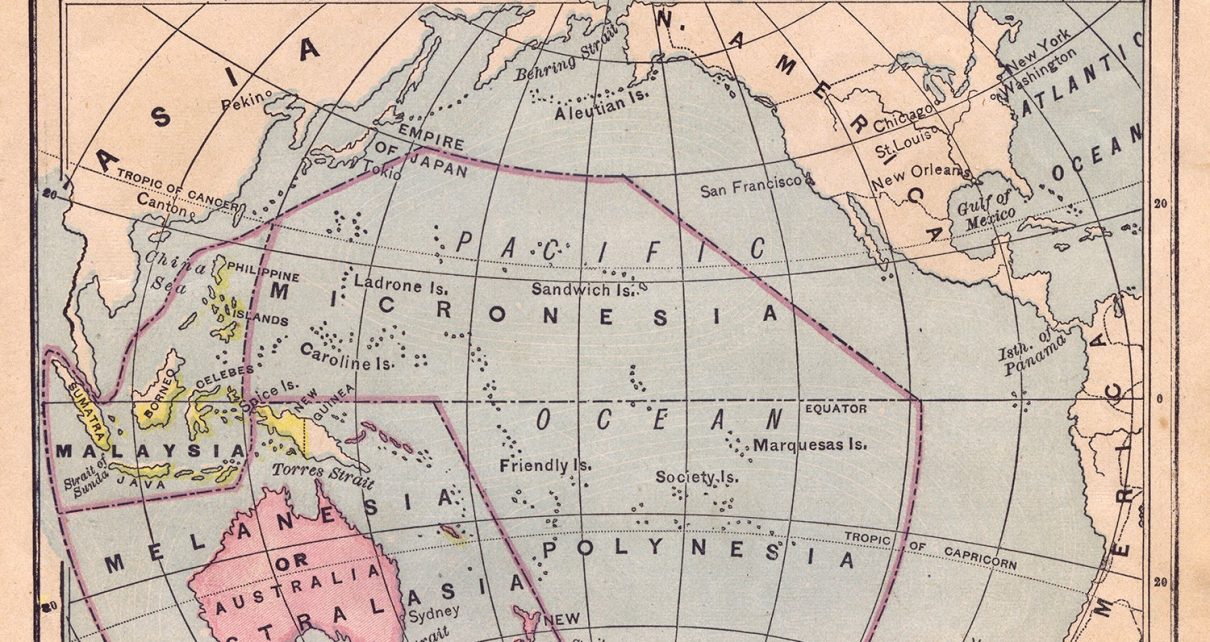

One-hundred-one days and 4,300 nautical miles later, his raft reached French Polynesia. The expedition didn’t really prove anything other than that the feat was possible. And most scholars agreed then and now that the Pacific islands were gradually settled from the other direction, by people traveling from East Asia.

But a new study suggests that, almost 900 years ago, Polynesians and Native South Americans did make contact—and traces of that encounter live on in the genes of Polynesians today.

“Whether the people were physically standing on an island in Polynesia when they began mingling—or whether they were on the coast of South America—we can’t say.”

Alex Ioannidis, a computational scientist and geneticist at Stanford University. His team compared the DNA of 800 individuals from 17 Pacific islands and 15 Pacific Coast Native American groups. And they discovered, within the genomes of modern-day Polynesians, snippets of DNA typically found in Native Americans.

“What we found is it’s actually a very similar sequence of DNA that they all share. That’s not explained otherwise than having a common ancestor in recent times.”

That ancestor likely came from the region of present-day Colombia or Ecuador, says co-author Andres Moreno-Estrada, of Mexico’s National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity. And the similarity of that sequence across Polynesians suggests only a single contact occurred. Based on the lengths of those DNA segments in modern individuals, the scientists were able to pin a possible date on the meeting: around the year 1150.

The study is in the journal Nature. [Alexander G. Ioannidis et al, Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement]

It’s important to note that while the finding does imply the two cultures met, it doesn’t say anything about which culture initiated the contact. And it certainly doesn’t support Heyerdahl’s controversial theory that Polynesian culture derives from settlers from South America.

However, Ioannidis points out that the discovery aligns with some non-genetic observations. For example, the sweet potato—a South American crop—is found in Polynesia, but how it got there is less clear. This study could provide an explanation.

“The other interesting thing about the sweet potato, is the word used for it in some of the Polynesian languages is very close to the word used for it in some of the northwestern South American languages, including along the coast of Ecuador. People have noticed that before, and it’s very interesting in light of what we found.”

Moreno-Estrada says the findings are valuable to anthropologists, but his primary interest was relaying the results back to the Polynesians who took part in the study.

“They were really excited knowing about their own history, and getting a picture of really what has been preserved in the DNA in respect to their ancestors.”

—Christopher Intagliata

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]