To us humans, climate change feels like something that’s happening to the atmosphere. But most of the action is actually at sea—about 90 percent of the heat that gets trapped by greenhouse gases is absorbed by the ocean.

“So it’s really important to track that energy in the climate system and track the warming of the ocean.”

Jörn Callies, an oceanographer at Caltech.

Of course, the ocean is really big, and taking its temperature is hard. Satellites give information about the surface, and scientists have launched drifting devices that measure conditions in the upper mile of water. But researchers still struggle to collect data from the deep ocean, and to detect the long-term trends underlying day-to-day variations in temperature.

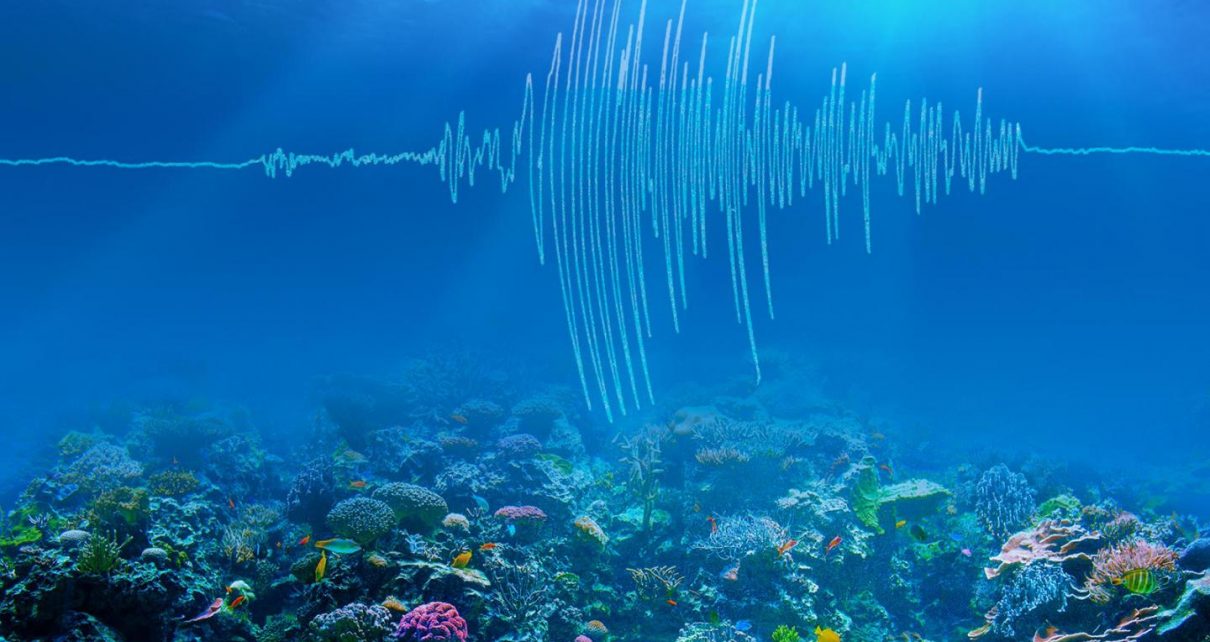

Now, however, scientists have developed a new technique that allows them to measure temperature changes across entire ocean basins. The idea dates back to the 1970s, when researchers first proposed using sound waves to study ocean warming—because the speed of sound through water depends on the physical properties of that water, which are related to temperature.

“And roughly, if we warm up the ocean temperature by one degree, the sound speed change—it would be four meters per second. And this is a very sensitive change.”

Wenbo Wu, a seismologist also at Caltech, who led the study. That one degree he mentioned is a Celsius degree.

Researchers originally proposed using artificial sound sources, but that notion got nixed because of concerns about the impacts on marine animals. In the new study, however, Wu, Callies and their colleagues show they can use the sounds produced by earthquakes instead.

In an earthquake, some vibrations bounce off the seafloor and turn into sound waves that get picked up by seismometers and underwater microphones.

The researchers looked at the travel times of these sound waves for 2,000 pairs of earthquakes that occurred in the East Indian Ocean between 2005 and 2016. Each earthquake pair happened in the same place but at different times, allowing the researchers to measure how much the sound waves sped up.

The analysis revealed that the waves traveled a few tenths of a second faster in more recent quakes than in older ones—a difference that translates to a warming trend of 0.04 degrees Celsius per decade.

Four one-hundredths of a degree may not sound like a lot, but it represents a huge amount of heat—considering it’s the change in a body of water almost 2,000 miles wide and several miles deep.

The warming is also substantially higher than the rate reported in previous studies, although Callies says not to put too much stock in those discrepancies.

“We don’t know whether that is the general finding—whether that only occurs here in this region at this time—or whether that is something we’ll find in other regions as well. We just don’t have the data yet.”

The study is in the journal Science. [Wenbo Wu et al, Seismic ocean thermometry]

Callies and Wu say that this approach may even enable scientists to gauge historical temperature changes by studying data from much older earthquakes. In other words, you could say that the method is sound.

—Julia Rosen

(The above text is a transcript of this podcast)